SPECIAL GUESTS // The Body, the Law, and the Scalpel: Geneva’s Unfolding Secret (16th Century)

A brief summary

Welcome to “Really, Calvin – is this an ideal life? A historical podcast.” Today, we’re delighted to share a special episode by our friend Isabella Watt, co-editor of the Registers of the Genevan Consistory in the time of Calvin. She brings us a surprising and colorful story at the crossroads of medicine, faith, and the human body: the moving case of Estienna Costel and Jean Cugnard—a 16th‑century Genevan couple whose story exposes the often pitiless way Calvinist society viewed sexuality and the female body.

Before diving into their intimate drama, let’s step back for some context. Since antiquity, medical and surgical treatises have shaped how people understood the body and its functions. Galen and Hippocrates still reigned supreme, their theories inspiring a humoral medicine in which health depended on the balance of bodily fluids. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, writings on female anatomy became more numerous—steeped in taboos, censorship, and the persistent idea that the female body was merely an inverted version of the male.

But in Calvin’s 16th‑century Geneva, these theories took on flesh in the person of Estienna Costel. Her husband, Jean Cugnard, sought a divorce: she suffered from a condition called arctitudo, a narrowing of the vaginal passage that made intercourse impossible and unbearably painful. The case shook Genevan institutions—the Consistory and the Lesser Council clashed over how to handle it, armed with reports from barber‑surgeons and midwives. Calvin, ever the logician, ruled the marriage invalid since it had never been consummated. But the Lesser Council took a different stance—one that was, shall we say, surgical. A solution so bold, even dangerous, that it leaves today’s listeners speechless.

In this episode, we delve into one of the most perplexing trials of Reformation‑era Geneva: where theology, anatomy, and conjugal violence intersect. How did the civil and ecclesiastical courts of Calvin’s time attempt to “repair” an impossible marriage?

Listen to the episode

If you prefer another audio platform (Spotify, Podcast Addict, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Overcast...), click here!

Script

Speaker #0 - Welcome back to the Deep Dive.

Speaker #1 - Today we're stepping away from broader themes and digging into something really specific, really personal. We've got our hands on court transcripts from 16th century Geneva. These are from the Registre du Consistoire de Genève. And our mission isn't about high theology today. It's about seeing how the strict moral oversight of the Reformation played out right inside people's homes. You know, when you think of Calvin's Geneva, maybe you picture debates about doctrine, but the Consistory, this powerful court of ministers and elders, they were just as worried about whether you were, well, doing your chores or fulfilling your marital duties. And this whole deep dive revolves around one incredibly intense, years-long marital fight between a hatter named Jean Cugnard and Estienna Costel, an innkeeper's daughter. And the entire conflict, it boils down to the failure, the physical failure of one basic conjugal duty.

Speaker #0 - Exactly. And what makes this case just fascinating, I think, and so useful for us... is that you see this sort of iron will of the Reformation, this demand for order and conformity smashing right up against a really messy private anatomical problem. It's amazing how this one single case file shines a light on 16th century marriage law, the pretty strange state of medical knowledge back then, and it even pulls in John Calvin himself to weigh in on divorce. Okay, let's really unpack this collision between spiritual law and the physical body. Where does it start?

Speaker #1 - Right, so the story kicks off in July 1562. The husband, Jean Cunard, goes straight to the consistory. He wants a separation. He paints this picture of Estienna being totally rebellious, disobedient, contrary, won't sleep in the same bed, and specifically refuses what the court calls the "devoir de femme", the wife's duty. He's claiming complete non-consummation. And we get these little glimpses into just how bad things were at home. Estienna actually admitted throwing out some meat he bought. Her defense was full of vermin.

Speaker #0 - Right. But the consistory zeroes in on the main issue, the lack of consummation. She admitted it. They hadn't had "sa compagnie", his company, meaning intercourse. And at this stage, you see, the consistory treats it purely as her fault, a moral failing, a kind of rebellion against the natural order. Marriage was absolutely fundamental to civic life, spiritual life in Geneva. Estienna was seen as shaking that foundation.

Speaker #1 - So what did they do? Tell her off.

Speaker #0 - Oh, much more than that. The reaction was swift and pretty uncompromising. They ordered her flat out to perform her duty "de jour et de nuit", day and night.

Speaker #1 - Day and night, wow.

Speaker #0 - Yes, under threat of punishment, "chastier". And they weren't bluffing. When she still refused, they took away her right to communion, the "Cène", and then they recommended something really extreme.

Speaker #1 - Okay, what?

Speaker #0 - That she be put in a "croton". Now, nobody's entirely sure what a "croton" was, but it sounds like a particularly nasty, deep, dark kind of prison cell.

Speaker #1 - They wanted to put her in a dungeon to scare her into sleeping with her husband.

Speaker #0 - That was the explicit goal. The record says it was to induce her "à rendre devoir de femme envers son mari", to make her render her wifely duty to her husband. It sounds brutal to us, but it shows just how seriously they took marital compliance.

Speaker #1 - That's chilling. So the pressure is intense. What happens next? Does she give in?

Speaker #0 - Well, this is where the story takes a sharp turn. Estienna gets hauled before the council itself. And her story changes completely.

Speaker #1 - How so?

Speaker #0 - It's no longer about rebellion or disobedience. Now it's about impossibility. She says, look, she's willing to go back to him, but she's simply incapable of having "sa compagnie". She physically cannot have intercourse with him.

Speaker #1 - Ah, so it shifts from won't to can't.

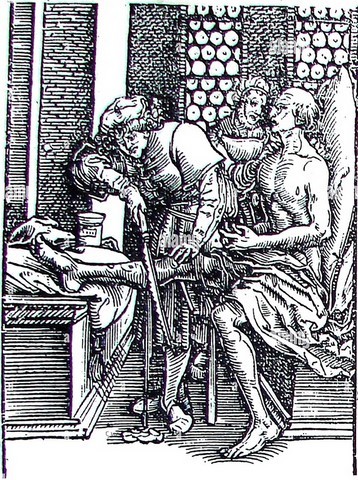

Speaker #0 - Exactly. And her mother actually backs this up. She testifies that she'd already taken Estienna to see a local expert, a "barbier ou/soit chirurgien", a barber or a surgeon, to figure out the problem.

Speaker #1 - And what did the surgeon say?

Speaker #0 - Nothing helpful. The mother reported that he needs shuranko and rest (?). He basically knew nothing, couldn't figure it out.

Speaker #1 - Why not? Didn't they understand basic anatomy?

Speaker #0 - Well, that's the crux of it. You have to remember, 16th century medicine and law. For female impotence, impotentia coiandi, the traditional legal category under canon law wasn't about desire or anything psychological. It was physical, usually diagnosed as arctitudo.

Speaker #1 - Arctitudo?

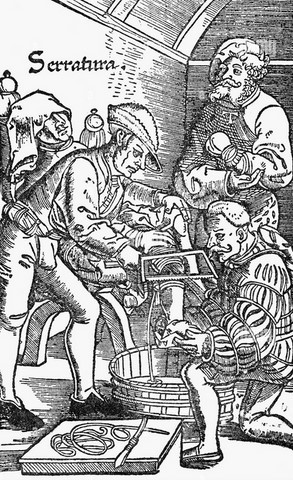

Speaker #0 - Yeah, it means extreme narrowness or tightness of the vagina. A physical blockage that prevents intercourse and, crucially, prevents generation having children. That was the key concern. But diagnosing it was tough. Surgery was often seen as a kind of low-status craft then. And a lot of the university-trained physicians, they were still working off ideas from ancient Greece, like Galen's one-sex model.

Speaker #1 - One-sex model.

Speaker #0 - Yeah, the idea that female organs were just sort of inverted, imperfect versions of male ones. So understanding unique female anatomy, it lagged way behind. If all you can imagine is a blockage like actitudo and you don't have the tools or maybe even the willingness to properly examine, well, the local guy comes up empty.

Speaker #1 - OK, so a legal problem hinging on a medical mystery that the local surgeon couldn't solve. How did they move forward?

Speaker #0 - The breakthrough comes right at the end of 1562, December 31st. The syndic, a chief magistrate, reports that Estianna has been examined again, but this time by "sages-femmes".

Speaker #1 - Midwives.

Speaker #0 - Exactly. And midwives, you see, often had much more practical hands-on experience with female bodies than many male surgeons or academic physicians.

Speaker #1 - And what did the midwives find?

Speaker #0 - This changed everything. Their report was clear. She was "fort estroite et comme inabile", very narrow and sort of unfit for intercourse.

Speaker #1 - They gave specifics.

Speaker #0 - They did. They noted she couldn't even tolerate the insertion of a "petit doigt", a small finger.

Speaker #1 - Wow, that's pretty definitive physical evidence.

Speaker #0 - Absolutely. And that concrete proof, it instantly shifts the whole case. It's not about moral failure anymore. It's about anatomy failing the requirements of the marriage contract. This becomes a canonical issue.

Speaker #1 - So what does the council do with this finding?

Speaker #0 - They go straight to the top. They consult the main man in Geneva, Jean Calvin himself.

Speaker #1 - Right, the ultimate authority. What did Calvin say when he heard the midwives report?

Speaker #0 - Calvin's response was direct and cut right to the heart of the Reformation view of marriage. He declared, and I'm quoting the essence here, "que ce n'est pas mariage quand le mari et la femme ne peuvent avoir compagnie ensemble, qu'un tel mariage doit être déclaré nul".

Speaker #1 - Meaning?

Speaker #0 - Meaning, basically, if the husband and wife cannot have physical company together, if they can't consummate the marriage, then it is not a marriage. It has to be declared null, void, end of story. For Calvin, consummation was absolutely central.

Speaker #1 - Okay. So Calvin rules, annulled the marriage, problem solved.

Speaker #0 - You would absolutely think so. Clear ruling from the top authority based on physical proof. But this is where the story takes another, frankly, quite startling turn.

Speaker #1 - What happened?

Speaker #0 - Instead of just processing the annulment, the Council, well, they hesitated and they proposed something else entirely, something radical.

Speaker #1 - Which was?

Speaker #0 - They suggested consulting more experts, medicines, "chirurgiens", doctors and surgeons to see if, and get this, if there was a way to give Estienna an "autre ouverture que celle de nature".

Speaker #1 - Another opening than that of nature. They mean surgically.

Speaker #0 - Yes. They suggested it could be done "artificiellement". They were seriously proposing surgery to essentially reconstruct or enlarge her vagina to make intercourse possible.

Speaker #1 - Wait, surgery in the 1560s? For that? That sounds incredibly dangerous. Borderline experimental.

Speaker #0 - Oh, absolutely extraordinary for the time. Surgery was brutal. No effective anesthesia. Infection was almost guaranteed. The risks were immense, especially for anything internal or intimate. Anatomical knowledge was patchy, and there were huge taboos around female genitalia. You even see censorship in anatomy books from the era. So the idea of doing this kind of, well, early plastic surgery on the vagina to fix arctitudo, it was incredibly daring. You had surgeons like Ambroise Perret around then who believed surgery should repair the defects of nature. But this, this was... pushing that idea to an extreme, highly risky place.

Speaker #1 - So why? Why even float this incredibly dangerous idea when Calvin had already given them the hour to annul the marriage?

Speaker #0 - That is the million dollar question, isn't it? It suggests there was this immense pressure, maybe from the council itself, to preserve the marriage contract at almost any cost. That social pillar, that civic building block seems so important that they'd contemplate radical, life-threatening intervention rather than just dissolve it.

Speaker #1 - It seems like the ideal of the unbreakable marriage contract almost trumps the actual physical reality and even Calvin's theological ruling.

Speaker #0 - It certainly looks that way. The drive, to fix the body to fit the contract rather than voiding the contract because the body couldn't comply. The social order seemed desperate for a physical fix, even a risky one.

Speaker #1 - So did they actually try to find surgeons? Did this proceed?

Speaker #0 - No. And the person who stopped it wasn't a doctor worried about the risks. or a minister citing Calvin, it was the husband, Jean Cugnard.

Speaker #1 - Cugnard refused, after all his complaints.

Speaker #0 - He flat out refused. In March 1563, the council ordered him to take Estianna to the surgeons, and he refused to comply.

Speaker #1 - Why? What was his reason?

Speaker #0 - His reason tells you so much about gender, shame, and the idea of a wife back then. He said quite clearly "il ne voudroit pas une femme qui aura esté maniée par les chirurgiens et les barbiers".

Speaker #1 - He wouldn't want a wife who had been... Handled by surgeons and barbers.

Speaker #0 - Exactly. Mainy handled, manipulated the very idea of male surgeons examining and altering his wife's intimate anatomy, even to potentially fix the marriage. It destroyed her value, her purity in his eyes.

Speaker #1 - So his sense of propriety or maybe ownership over her body was stronger than his desire to have the marriage consummated or validated?

Speaker #0 - It seems so. That notion of the untouched, unmanipulated female body, at least by those hands, trumped everything else, the consistory's pressure, the Council's order, maybe even his own initial demands. It's a real window into the mindset of the time.

Speaker #1 - So what happened to them in the end? With the surgery off the table, did they finally get the annulment Calvin recommended?

Speaker #0 - Well, like a lot of these historical deep dives, the ending isn't perfectly neat. The surgical idea dies, but the marriage doesn't immediately dissolve either. The consistory records show the case just kind of drags on through 1564. It actually reversed back to the earlier kinds of complaints, accusations of domestic strife, Cugnard hitting her, Estianna calling him a Lauren, a thief, standard marital misery almost.

Speaker #1 - So they didn't separate or annul.

Speaker #0 - We know they were eventually readmitted to communion. which suggests some kind of reconciliation or at least a truce enforced by the consistory. But whether the marriage was ever formally declared null, as Calvin advised, or if they just remained legally bound but miserable and probably separate, the records we have just don't give us that final definitive answer. It kind of fizzles out.

Speaker #1 - Wow. What a story. So stepping back, what are the big takeaways from Estianna Costel's case?

Speaker #0 - I think it's this incredible snapshot of a moment where everything collided. You have this strict spiritual law from Calvin. saying non-consummation voids the marriage. You have the physical evidence from the midwives confirming the impossibility. And yet you have this powerful social and institutional pressure pushing for a physical, even surgical fix. It really highlights how, for the Reformation state in Geneva, the body's performance, especially sexual performance within marriage, was tied directly to civic order and spiritual compliance.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, it starkly reveals the immense pressure on women back then to basically be sexually functional, according to a very narrow definition. And the extreme measures considered when a woman's body physically couldn't meet that standard.

Speaker #0 - Absolutely. The fact that they even contemplated such a dangerous novel surgery speaks volumes about the desperation to uphold the marriage contract.

Speaker #1 - So any final thought for us to chew on from this?

Speaker #0 - Yeah, here's something interesting to consider. In 1563, Estianna's problem, arctitudo, was seen as purely physical. anatomical, a mechanical flaw that theoretically you might even be able to surgically repair, however risky. But fast forward a couple hundred years, medical thinking shifts dramatically. When doctors encounter non-consummation, the focus moves away from just the physical narrowness. It starts to become about the woman's mind, her desire, or lack thereof. It morphs into ideas about the soul, the moral dimension, and eventually lands on diagnoses like frigidity.

Speaker #1 - Ah, so from a potentially fixable physical defect to a psychological or moral failing.

Speaker #0 - Exactly. So maybe Estienna's case, with its proposed surgical fix, represents one of the last moments where this kind of female sexual incapacity was viewed almost entirely as an anatomical engineering problem, right before the medical world started classifying it very differently as a problem of will or desire or character. It's a fascinating pivot point.

Sources

In this episode, we invited you to discover the eventful life of Estienna Costel and her husband Jean Cugnard through an in-depth study of primary sources preserved at the State Archives of Geneva. These sources mainly consist of the registers of the Consistory, as well as documents from the Criminal Jurisdiction.

All these references are accessible via the online database of the Consistory of Geneva at the following address: https://geneve16e.ch. Simply enter the name of the individual you are researching in the search bar. It should be noted that this database is a working tool and not a platform of finalized or formatted sources.

Furthermore, only references to volume 19 include page numbers from the printed edition of the Registers of the Consistory of Geneva during Calvin’s time. Volumes 20 and 21, covering the period up to Calvin’s death in 1564, are still being prepared and have not yet been printed.

Finally, we will mention two brief publications from May 1564, although these are not directly related to this intriguing case.

The complete list of the passages studied, which enabled us to develop a precise and well-documented account, now follows.

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 19, f. 106v, p. 235-236 (16 juillet 1562)

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 19, f. 132, p. 285 (3 septembre 1562)

- A.E.G., Jur. Pen. A3, f. 61v (7 septembre 1562)

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 19, f. 157v, p. 332 (15 octobre 1562)

- A.E.G., Jur. Pen A3, f. 72v (19 octobre 1562)

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 19, f. 181, p. 380 (26 novembre 1562)

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 19, f. 198v, p. 417 (24 décembre 1562)

- A.E.G., Jur. Pen. A3, f. 81v (30 novembre 1562)

- A.E.G., Jur. Pen. A3, f. 92v (28 decembre 1562)

- A.E.G., Jur. Pen. A3, f. 94 (31 decembre 1562)

- A.E.G., Jur. Pen. A3, f. 95 (1 janvier 1563)

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 20, f. 11v (4 mars 1563)

- A.E.G., Jur. Pen. A3, f. 5v (8 mars 1563)

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 20, f. 54v (20 mai 1563)

- A.E.G., Jur. Pen. A3, f. 24 (24 mai 1563)

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 20, f. 113 (26 août 1563)

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 20, f. 129v (9 septembre 1563)

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 21, f. 63v (16 mai 1564): Jehan Cugnard et sa femme appellez pour leur maulvais mesnage. Le mary dict qu’il l’appella quand elle jouoit aux quilles, mais elle ne voullut pas venir, et pour ce il luy remonstra sa faulte, à quoy elle cria fort haultement. Sur ce il luy bailla ung soufflet. Elle dict cela estre veritable. L’advis est de les admonester de vivre en paix.

- A.E.G., R.Consist. 21, f. 67 (18 mai 1564): Jehan Main, Rollet Mege, sa femme, Jehan Cugnard, sa femme, Jehan Abram, Jehan Cornet requierent estre receuz à la Cene que leur a esté deffendue à tous particullierement. L’advis est de leur dire qu’ilz seront receuz, excepté led. Abram, qui a dict qu’il ne s’en souvient pas, et Mege et sa femme ranvoyez à Monsieur Copus.

And much more

Here are a few ways to broaden your knowledge and discover other archives:

- Wendy SUFFIELD, "The mysteries behind a mediaeval manuscript of women'sills", in Library blog of the Royal College of surgeons of England, 15/01/2024, online web

- Mariana Juliana de OLIVEIRA SOARES, "As receitas médicas de Hannah Woolley: prática cotidiana e autoridade feminina na Inglaterra do século XVII", História, ciências, saúde-manguinhos, n° 30 (2023), online: there is also an English version web

- Blanca ESPINA-JEREZ et alii, "Women health providers: materials on cures, remedies and sexuality in inquisitorial processes (15th-18th century)", Frontiers in psychology, vol. 14 (2023), online web

- Rebecca FLEMMING, "The classical clitoris: part 1", Eugesta, journal of gender studies in Antiquity, n° 12 (2022), online web

- Kate BAJOREK, "The wandering womb and other lady problems. The Trotula and twelfth-century female inferiority", Chronos. The undergraduate history journal, n° 14 (2020), pp. 7-15 web

- Peter CRYLE, "Female impotence in Nineteenth-Century France: a study in gendered sexual pathology", News and papers from the George Rudé Seminar, Brisbane (AU): The George Rudé Society, 2017, pp. 80-91 web

- Lauren KASSELL, "Medical Understanding of the body, c. 1500-1700", in Sarah TOULAHAN / Kate FISHER (ed.), The Routledge history of sex and the body, 1500 to present, New York: Routledge, 2013, pp. 57-74 [608 p.]

- Julia M. GARRETT, "Witchcraft and sexual knowledge in Early Modern England", Journal of Early Modern cultural studies, vol. 13, n° 1 (winter 2013), pp. 32-72 web

- Peter CRYLE / Alison MOORE, Frigidity. An intellectual history, Basingstoke (US): Palgrave Macmillan, 12/2011, 317 p.

- Katherine ANGEL, "The history of Female sexual dysfunction as a mental disorder in the 20th century", Current opinion in psychiatry, vol. 23, n° 6 (11/2010), pp. 536-541 web

- John STUDD / Anneliese SCHQENKHAGEN, "The historical response to female sexuality", Maturitas, vol. 63, n° 2 (20/06/2009), pp. 107-111 web

- Lesley SMITH, "The mechanics of female sexual performance in the 16th century", Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care, vol. 35, n° 2 (2009), pp. 127-128 web

- Helen KING, Midwifery, obstetrics and the rise of gynaecology: the uses of a sixteenth-century compendium, New York: Routledge, 07/2007, 238 p.

- Edward BEHREND-MARTINEZ, "Female sexual potency in a Spanish church court, 1673-1735", Law and history review, vol. 24, n° 2 (summer 2006), pp. 297-330 web

- Kenneth BORRIS, Same-Sex desire in the English Renaissance: a sourcebook of texts, 1470-1650, New York: Routledge, 2004, 400 p.: "Medicine", pp. 115-122

- Jane SHARP / Elaine HOBBY, The midwives book: or the whole art of midwifry discovered, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 09/1999, 368 p.

- Paster GAIL KERN, The body embarrassed: drama and the disciplines of shame in Early Modern England, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993, 312 p.

- Ann DALLY, Women under the knife: a history of surgery, London: Hutchinson Radious & Co, 1991, 289 p.

- Virginia MASON VAUGHAN, "Daughters of the game: Troilus and Cressida and the sexual discourses of 16th-century England", Women's studies international forum, vol. 13, n° 3 (1990), pp. 209-220 web

- Nancy G. SIRAISI, Medieval and Early Renaissance medicine: an introduction to knowledge and practice, Chicago: University of Chicago, 1990, 264 p.

- Thomas G. BENEDEK, "Beliefs about human sexual function in the Middle Ages and Renaissance", in Douglas RADCLIFF-UMSTEAD (ed.), Human sexuality in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Pittsburg: Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 1978, 193 p.

- C.D. O'MALLEY, "Helkiah Crooke, M.D., F.R.C.P., 1576-1648", Bulletin of the history of medicine, vol. 42, n° 1 (01-02/1968), pp. 1-18 web

RCnum PROJECT

This historical popularization podcast is developed as part of the interdisciplinary project entitled "A semantic and multilingual online edition of the Registers of the Council of Geneva / 1545-1550" (RCnum) and developed by the University of Geneva (UNIGE), as part of funding from the Swiss National Scientific Research Fund (SNSF). For more information: https://www.unige.ch/registresconseilge/en.