Meat, Power, and Politics: Geneva’s Butcher Games (1536-1550)

A brief summary

Welcome to Really Calvin, is this an ideal life? A historical podcast. In today's episode, 'Meat, Power, and Rebellion: Geneva's Butchers vs. Authority (1536-1550),' we dive into the simmering tensions of Reformation-era Geneva. Picture this: a city caught between Calvin's strict moral order and a defiant butchers' guild determined to carve out their own rules. From price disputes to tax rebellions and even fights over prime real estate for their shops, the butchers weren’t afraid to challenge the city’s rulers. Add in some drama with roast houses and a few creative punishments, and you’ve got a recipe for a meaty historical showdown. Let’s explore how this battle over beef shaped Geneva’s political landscape.

Listen to the episode

If you prefer another audio platform (Spotify, Podcast Addict, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Overcast...), click here!

*******

Script

Speaker #0 - All right, so you're back with us for another deep dive. And today we're going somewhere really interesting. We're going to 16th century Geneva.

Speaker #1 - Yeah.

Speaker #0 - And we're going to be using the "Registres du Conseil", which is like their council minutes, basically.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, exactly.

Speaker #0 - And we're going to be looking at something kind of surprising. I think something that I hadn't really thought much about before, but really, really fascinating once you kind of get into the details. And that is butchers and butcheries.

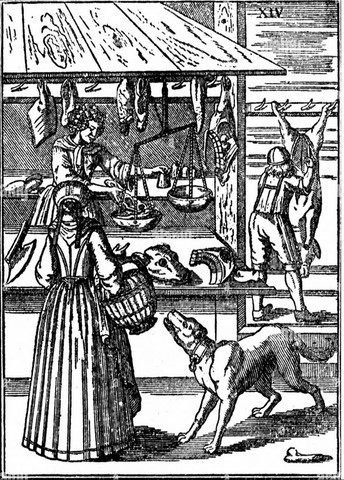

Speaker #1 - That's right. We're diving into this section called "Viande et boucherie, écorcheries, rôtisseries, triperies", which kind of covers the whole gamut of meat in 16th century Geneva. But we're going to focus squarely on the butchers. And what's really amazing is when you look at these records, the most abundant animal-related mentions are all about food. Meat in particular.

Speaker #0 - Yeah, that's right. I mean, when you think about it, it's like, well, yeah, of course. But it's just sort of funny to think about, like, that's what they decided to record. It's like the most important thing that they're dealing with animals for is like eating them pretty much.

Speaker #1 - Absolutely. And it's not even a given, right? Like even the people who are compiling these registers are debating amongst themselves, like, is this too mundane? Should we even be writing this down for posterity or should we stick to the big issues of religion and finance and these kinds of things? And thankfully for us, they did include these more everyday elements. And so we have this incredible window into the daily lives of people.

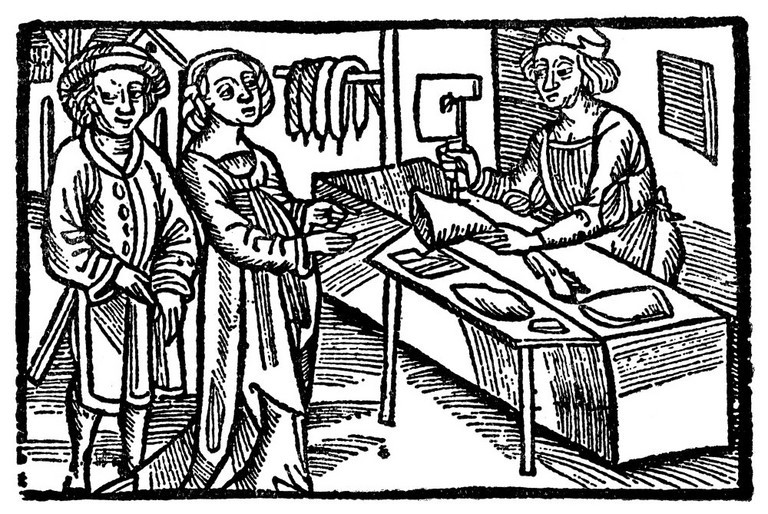

Speaker #0 - Yeah. And I love that the mundane stuff is really where it's at, I think. So let's talk about, you know, the actual butchery, the butchering. You know, it's not like you could just set up shop anywhere in town. There was a lot of regulation around this, wasn't there?

Speaker #1 - Yeah, there's all kinds of regulations. Like prices are set by the authorities. They have a tax, a gabelle, they call it, which is levied on every animal that's slaughtered. So it's a way for them to get revenue, obviously, and they even regulate the rent. for the butcher stalls themselves.

Speaker #0 - Oh, wow.

Speaker #1 - So they control the price of the meat. They control where the meat can be sold. Right. And they even control kind of how much the butchers are making by setting the rent for the stalls.

Speaker #0 - So it sounds like they were really trying to control the meat supply, which makes sense. It's such an important commodity. Were there any issues that they were trying to target with all this regulation or things that were coming up over and over again?

Speaker #1 - Yeah. So unfair competition was a big concern, which isn't surprising when you've got you know, lots of different people trying to make a living. They regulated where the animals could be slaughtered. They generally had to be slaughtered either within the butcher's premises or at designated *écorcheries", which were basically slaughterhouses outside of the city walls, probably for reasons of sanitation.

Speaker #0 - Okay.

Speaker #1 - And then there's this interesting little tidbit. Four times a year, butchers were entitled to a gratuity of tongues.

Speaker #0 - Free tongues.

Speaker #1 - Free tongues. four times a year.

Speaker #0 - Wow. I like that perk.

Speaker #1 - Right. It makes you wonder about like what was the relative value of different parts of the animal and how are those kind of distributed among the population?

Speaker #0 - So interesting. So it sounds like the butchers, you know, weren't just passive in this process of all this regulation. They actually had their own organization.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. They had the "Corporation des bouchers", which was a guild, basically, and it had a lot of influence.

Speaker #0 - That sounds like they did.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, they would challenge decisions that were made by the Council of 200, especially around pricing. Like when the council would set prices that the butchers didn't think were fair, they would say, no, we're not going to sell at this price.

Speaker #0 - Wow, so they could really push back against the authorities.

Speaker #1 - They could.

Speaker #0 - That's amazing.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, and there's a really great example. In 1540, the Grand Conseil actually decreed that any butcher who refused to swear a prescribed oath but kept selling meat would be punished.

Speaker #0 - So they were really trying to clamp down.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, they were trying to get control over these butchers.

Speaker #0 - Okay, so how did all this back and forth, this tension affect the average Genevan? What did they have to pay for their meat?

Speaker #1 - Well, the records actually give us prices for beef and mutton over several decades.

Speaker #0 - Oh, wow.

Speaker #1 - From 1513 to 1549. And you can really see the market responding to different factors. Sometimes prices go up, sometimes they go down. And the authorities are trying to control that volatility with these regulations. Now, one interesting thing is that butchers were only allowed to sell by weight. They couldn't sell by the piece, which makes sense when you think about it from a taxation and control perspective. They want to be able to track exactly how much meat is being sold and they want to make sure that everyone's being taxed fairly. And later on in the records, actually, it says explicitly that selling by the piece is prohibited.

Speaker #0 - That's so interesting. OK, so let's talk about this "amodiation de la chair", which is the meat lease. What was that all about?

Speaker #1 - Yeah, so the "amodiation de la chair" is basically the city leasing out the right to sell meat. And collect the taxes within a certain area.

Speaker #0 - So they're selling the right to sell meat.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And individuals would bid on this, right? And we know, for example, that a guy named Claude Bernard held this lease in 1536. And actually, in the same year, he complains he can't pay the full amount because of the wars that are going on that are affecting the availability of meat.

Speaker #0 - So even back then, even essential goods like meat were subject to these big geopolitical forces.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, absolutely.

Speaker #0 - Really interesting. And this kind of ties into the meat tax that we talked about earlier, which also changed during this period.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, that's right. It went from being a percentage, a sue per florin of the meat's value to a per animal tax.

Speaker #0 - Oh, interesting.

Speaker #1 - And this happened in 1536 at the request of the butchers.

Speaker #0 - So the butchers themselves wanted this change.

Speaker #1 - They did. And we know that in April 1536, they set the initial rates for the different animals. The "boeuf massé", which is a male bovine. The "vache", the cow. "Mouton", which is mutton. "Veau", which is veal, and "porc", which is pork. And interestingly, these rates weren't set in stone immediately. There were adjustments within days. By April 12th, they had settled on final rates for beef cow, pork, mutton, ewe, and veal. And amazingly, those rates stayed pretty consistent over the following decades.

Speaker #0 - So they found a system that worked.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. It seems so.

Speaker #0 - Amazing. So were there taxes on other types of meat besides just, you know, the standard beef and pork and all that?

Speaker #1 - Yes. Bovine tongues were taxed separately. And this actually led to a conflict in 1525 between Genevan butchers and the Duke of Savoy over who had the right to collect this tax. And there were also taxes on what they call secondary meats and fat meats like beef, which was taxed at a higher rate.

Speaker #0 - Interesting.

Speaker #1 - And actually there's a decree from 1521 that gives us a much broader picture of the kinds of meat that people were eating beyond beef, cow, mutton, sheep, pork, and veal. They also had poultry and game.

Speaker #0 - Oh, so they were eating a pretty diverse diet, at least some people were.

Speaker #1 - It seems so.

Speaker #0 - Interesting... So let's talk about where you could actually find these butcheries in Geneva. Where were they located?

Speaker #1 - Well, in 1535, there were three confirmed butcheries. There was one at "Longemale", one at "Pont du Rhône", and one at "Place des Juifs", which was also called "Juiverie" or "Grand Mezel". Near the Saint-Germain church.

Speaker #0 - Just three for the whole city.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, that's all we have records of.

Speaker #0 - Wow, so those must have been pretty important places.

Speaker #1 - They must have been. And the location of the main butchery, the "Grande Boucherie", was actually a bit of a controversy.

Speaker #0 - Oh, really?

Speaker #1 - Yeah. In April 1536, the Grand Council decided to move it near the Maison de la Ville, because they said the "Place de l'évêché" was an unfavorable location.

Speaker #0 - You can just imagine the conversations about where the main butcher shop should be.

Speaker #1 - Right. Like, where is the best place for everyone to access this important service? And interestingly enough, within a year, there were discussions about moving it back to the original location. So it seems like the butchers had their own preferences and they weren't afraid to voice them.

Speaker #0 - Yeah, they weren't going to just take this lying down.

Speaker #1 - Exactly.

Speaker #0 - And another interesting point is that Saint-Gervais, despite having a large population, didn't have a butchery at all. And apparently that was for political reasons. They didn't trust the largely foreign inhabitants of Saint-Gervais.

Speaker #1 - Wow. So even something as basic as a butcher shop was tied up in politics.

Speaker #0 - Yeah, absolutely.

Speaker #1 - So we talked about taxes, we talked about leases, but what about rent? I mean, rent must have been a big expense for these butchers.

Speaker #0 - It was. And there's a really interesting example from mid-April 1536, where the Longemale butchers actually requested a rent reduction. They said they weren't selling as much meat because a lot of the Catholics had left Geneva and the suburbs had been destroyed.

Speaker #1 - So they were feeling the economic effects of these broader changes.

Speaker #0 - Yeah.

Speaker #1 - Interesting. And what did the authorities do?

Speaker #0 - They agreed to reduce the rent.

Speaker #1 - They did?

Speaker #0 - Yeah, at least for the first 12 benches, which are like the prime stalls. But in contrast, the butchers in Vanduvers were paying a much higher rent.

Speaker #1 - Oh, wow. So there were definitely discrepancies depending on your location. And were there any times when butchers just couldn't pay their rent at all? There are instances of that as well in the records where butchers are struggling to make ends meet.

Speaker #0 - Yeah, it sounds like a tough business.

Speaker #1 - It was.

Speaker #0 - So it sounds like a lot of regulations, a lot of challenges for the butchers. What about the consumers? Were there any measures in place to protect them?

Speaker #1 - Yeah, so they had officials whose job it was to oversee the butchers and make sure they were charging fair prices. Okay. And in 1537, there was actually a proposal to put scales in the Grande Boucherie, so they could weigh the meat in front of the customer.

Speaker #0 - So the customer knew they were getting what they paid for.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. It's a very early form of consumer protection.

Speaker #0 - That's really interesting.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. And it wasn't just about the prices. The butchers also got in trouble for trying to avoid paying their tithes on oats.

Speaker #0 - So they were really trying to make sure these butchers were following all the rules.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. They were trying to keep them honest.

Speaker #0 - And one other thing I thought was interesting is this idea of "liberty" for the butchers, which sounds good on the surface, but it actually came with a bit of a catch.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. So "liberty" meant that the butchers could set their own prices. But it also meant that they lost their exclusive right to sell meat.

Speaker #0 - Oh, so now they had competition.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. Foreigners were allowed to come in and sell meat at the same price.

Speaker #0 - So they had to choose between freedom and a monopoly.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, exactly.

Speaker #0 - That's fascinating.

Speaker #1 - Yeah.

Speaker #0 - So we've talked about taxes and leases and rent and all that. But there was also this other thing. The "offense des bouchers", which means the butcher's offenses lease. What was that all about?

Speaker #1 - Yeah. So this was basically the city leasing out the right to collect fines from butchers who broke the rules. And a guy named Louis Rommel was one of the early holders of this lease. And we know that in 1542 and 1543, they were paying a certain amount for this right to collect these fines.

Speaker #0 - And what kinds of things were the butchers getting fined for?

Speaker #1 - Well, they could get fined for selling above the set price. And the buyers could also get fined for paying more than the set price.

Speaker #0 - Oh, wow. So they went both ways.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, they were really trying to control the market. And they kept emphasizing that meat should be sold "au balances", at the scales.

Speaker #0 - So everything had to be weighed and measured.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. Transparency was key.

Speaker #0 - So with all these rules, all this oversight, there must have been some resistance from the butchers, right?

Speaker #1 - Absolutely. Absolutely. Resistance was a... constant problem.

Speaker #0 - In what ways?

Speaker #1 - Well sometimes they would just refuse to slaughter or sell meat at the fixed prices.

Speaker #0 - Really?

Speaker #1 - Yeah and in July 1544 the Seigneury actually had to order the public criers to announce the regulations and enforce them against the butchers.

Speaker #0 - They were really trying to crack down.

Speaker #1 - They were and there's even a pretty big scandal in April 1548.

Speaker #0 - Oh what happened?

Speaker #1 - Well, the butchers colluded. They actually signed a contract to avoid buying livestock from Berne's subjects.

Speaker #0 - Wow. So they were trying to control the supply?

Speaker #1 - Yeah, it was like a cartel.

Speaker #0 - And what happened?

Speaker #1 - Well, the authorities found out they arrested some of the butchers and they annulled the contract.

Speaker #0 - So they weren't messing around?

Speaker #1 - Nope.

Speaker #0 - Okay, so last question. Was there any kind of quality control for the meat?

Speaker #1 - Yeah. Believe it or not, there was. In October 1540, they actually decided to appoint two people in each butchery. whose job it was to inspect the meat and make sure it was good quality.

Speaker #0 - Wow. So they had like meat inspectors.

Speaker #1 - Exactly.

Speaker #0 - That's amazing. It sounds like they were really trying to protect the consumers.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, they were.

Speaker #0 - Wow. This has been so fascinating. I never would have thought that there would be so much to say about butchers in 16th century Geneva.

Speaker #1 - It's really amazing the level of detail that's in these records.

Speaker #0 - It really gives you a sense of what daily life was like back then. Yeah. All the challenge, all the regulations.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. And how important something as simple as meat was to the functioning of society.

Speaker #0 - Exactly. So it makes you think, doesn't it? Like how do those challenges compare to the challenges we face today with our food system?

Speaker #1 - Yeah. Like what's changed and what's stayed the same?

Speaker #0 - Yeah. Like are we still dealing with some of the same fundamental issues just in a different form?

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And it really highlights how important it is to understand the history of our food systems.

Speaker #0 - Absolutely. Because those historical forces are still shaping our lives today.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, so we encourage you to go and do some research, looking into the history of your own local food systems and see what you can find.

Speaker #0 - Yeah, you might be surprised by what you discover.

Speaker #1 - You might be.

Speaker #0 - All right, thanks for joining us for this deep dive.

Speaker #1 - Thanks for having me.

Speaker #0 - We'll see you next time.

Sources

This is an excerpt, translated into English, from our study entitled “Synthèse historique II: Les animaux à travers les Registres du Conseil de Genève (1536-1550)", published online, in French, in 2024. (web)

Too long to be included on this page, here is a summary:

This section explores in detail the conflictual relationship between the City of Geneva and the powerful butchers' guild during the period 1536 to 1550. The butchers, often bourgeois and members of the Councils, exerted considerable political influence, making it difficult to enforce the City's decisions concerning the meat trade. The main points of friction included the setting of official selling prices, the amount and method of collection of the gabelle (the tax on slaughtered animals), the rent of vices, and the location of butchers' shops. Butchers did not hesitate to defy the authorities, using supply limitation as a means of pressure.

Faced with this resistance, the City tried various means to assert its authority and regulate the meat market. In particular, it set up a system of amodiation of offenses, entrusting individuals with the control of butcheries and the collection of fines. However, this system ran into difficulties and was eventually replaced by inspection by the lieutenant. The question of the “freedom” claimed by butchers, allowing them to sell at whatever prices they wished, was a central point of conflict, as the City feared it would lose all control over taxation and the market. Measures were also taken concerning the slaughter of animals, initially imposed in public butcheries for reasons of hygiene, before being temporarily relaxed and then reinstated.

Finally, the section also addresses the situation of vendors of cooked meats (rotisseries), who had to take an oath and whose location was subject to decisions by the City Council, often in response to complaints from butchers who saw this as unfair competition. In conclusion, this period was marked by a constant struggle between the City and the butchers' guild, illustrating the challenges faced by the authorities in regulating an essential economic sector and enforcing their ordinances in the face of well-established corporate interests.

And much more

Some reading suggestions to discover the art of butchery and meat consumption under the Ancien Régime:

- Reynald ABAD, "Les tueries à Paris sous l'Ancien Régime ou pourquoi la capitale n'a pas été dotée d'abattoirs aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles", Histoire, économie et société, vol. 17, n° 4, 1998, pp. 649-676 web

- Rosemary BRANDAU, The butchering and processing of pork in eighteenth century Williamsburg, Williamsburg (VI): Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, 1984, online web

- Gilles CASTER, "Les cuirs bruts à Toulouse au XVIe siècle", Annales du Midi, vol. 90, n° 138-139, pp. 353-376 web

- Jean CATALO / Isabelle RODET-BELARBI / Yves LIGNEREUX, "Déchets de boucherie et alimentation au XIVe siècle à l'Hôpital du Pas à Rodez", Archéologie du Midi médiéval, n° 13, 1995, pp. 187-195 web

- G. CHAUDIEU, De la gigue d'ours au hamburger, ou la curieuse histoire de la viande, Chennevières (FR): Éditions de La Corpo, 1980, 203 p.

- Marco CICCHINI, "Viande politique et politiques de la viande. Genève au XVIIIe siècle", Carnets de bord, n° 15, 2008, pp. 18-27 web

- Valentina COSTANTINI, "On a red line across Europe: butchers and rebellions in fourteenth-century Siena", Social history, vol. 41, n° 1, 2016, pp. 72-92 web

- Bistra A. CVETKOVA, "Le service des celep et le ravitaillement en bétail dans l'Empire Ottoman (XVe-XVIIIe siècles)", Études historiques, n° 3, 1966, pp. 145-172

- Bistra A.. CVETKOVA, "Les celep et leur rôle dans la vie économique des Balkans à l'époque ottomane XVe-XVIIIe s.", in M.A. COOK, ed., Studies in the economic history of the Middle East, London, Oxford University Press, 1970, pp. 172-192

- C.D. DICHERSON, "Butchers as murderers in Renaissance Italy", in Trevor DEAN / K.J.P. LOWE, eds., Murder in Renaissance Italy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 289-308 web

- René FAVIER, "Le marché de la viande à Grenoble au XVIIIe siècle", Histoire, économie et société, vol. 13, n° 4, 1994, pp. 583-604 web

- Hayley Jane FOSTER, A zooarchaeological study of changing meat supply and butchery practices at medieval castles in England, Exeter (UK): University of Exeter, 2016, 331 p.: PhD thesis web

- Paul FREATHY / Iris THOMAS, "Hegemony and Protectionism in Bologna's meat trade: the role of visual imagery in reputation management", Enterprise and society, vol. 22, n° 2, 2021, pp. 566-592 web

- Antonino GIUFFRIDA, "Considerazioni sul consumo della carne a Palermo nei secoli XIV et XV", Mélanges de l'École française de Rome, vol. 87, n° 2, 1975, pp. 583-595 web

- Antony GREENWOOD, Istanbul's meat provisioning: a stuy of the Celepkesan system, Chicago: University of Chicago, 1988, 299 p.: unpublished PhD thesis

- Fabienne HUARD-HARDY, "L'approvisionnement carné de Paris du XIIe au XVIIIe siècle: la viande comme moteur de l'histoire", Actes des congrès nationaux des sociétés historiques et scientifiques, vol. 138, n° 10, pp. 36-45 web

- Iran KOKDAS, "Celeps", butchers, and the sheep: the worlds of meat in Istanbul in the sixteenth-seventeenth centuries, Istanbul: Sabanci University, 2007, 125 p.: master's thesis web

- Sylvain LETEUX, "Les formes d'intervention des pouvoirs publics dans l'approvisionnement en bestiaux de Paris: la Caisse de Poissy, de l'Ancien Régime au Second Empire", Revue d'études en agriculture et environnement, n° 74, 2005, pp. 49-78 web

- Sylvain LETEUX, "L'image des bouchers (XIIIe-XXe siècles): la recherche de l'honorabilité, entre fierté communautaire et occultation du sang", Images du travail, travail des images, n° 1, 2016, online web

- E. MALTEN et al., "Beef, butter, and broth: cooking in 16th century Sweden", Archeological and anthropological sciences, vol. 17, 2025, online web

- Philippe MEYZIE, "Une culture alimentaire protestante dans la France méridionale (XVIe-XVIIIe siècles)?", in Olivier CHRISTIN / Yves KRUMENACKER, eds., Les protestants à l'époque moderne: une approche anthropologique, Rennes (FR): Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2017, pp. 105-121 web

- Anne-Marie PIUZ, "À Genève, aux XVIe-XVIIIe siècles: bétail de Savoie, de Suisse et du Pays de Gex", in Charles HIGOUNET, ed., L'approvisionnement des villes. De l'Europe occidentale au Moyen Âge et aux Temps Modernes, Toulouse (FR): Presses universitaires du Midi / Comité départemental du tourisme du Gers, 1983, pp. 265-271 web

- Anne-Marie PIUZ, "Le marché du bétail et la consommation de la viande à Genève au XVIIIe siècle", Annales: économies, sociétés, civilisations,, vol. 30, n° 2-3, 1975, pp. 575-583 web

- Inna PÕLTSAM-JURJO, "Food and norms in 13th-16th century Estonia: meat and meat products", Eesti Arheoloogiaajakiri, vol. 27, n° 3, 2023, pp. 32-49 web

- Louis STOUFF, "La viande. Ravitaillement et consommation à Carpentras au XVe siècle", Annales: économies, sociétés, civilisations, vol. 24, n° 6, 1969, pp. 1431-1448 web

- Grace E. TSAI et al., "Bay salt in seventeenth century meat preservation: how ethnomicrobiology and experimental archaeology help us understand historical tastes", BJHS Themes, n° 7, 2022, pp. 63-93 web

- Sydney WATTS, Meat matters: butchers, politics, and market culture in eighteenth century Paris, New York : Boydell & Brewer / University of Rochester Press, 2006, 244 p.

- Philippe WOLFF, "Les bouchers de Toulouse du XIIe au XVe siècle", Annales du Midi, vol. 65, n° 23, 1953, pp. 375-393 web

*******

RCnum PROJECT

This historical popularization podcast is developed as part of the interdisciplinary project entitled "A semantic and multilingual online edition of the Registers of the Council of Geneva / 1545-1550" (RCnum) and developed by the University of Geneva (UNIGE), as part of funding from the Swiss National Scientific Research Fund (SNSF). For more information: https://www.unige.ch/registresconseilge/en.