Geneva's Golden Austerity: Calvin, Luxury, and the Reformation

A brief summary

Welcome to "Really Calvin, is this an ideal life? A historical podcast." In today's episode, we dive into the fascinating world of 16th-century Geneva in this captivating podcast exploring the complex relationship between luxury and austerity during the Reformation. We'll challenge the common perception of strict Calvinist austerity, revealing how sumptuary laws aimed for moderation rather than asceticism. Discover the meaning behind Geneva's motto "Post Tenebras Lux" (Light After Darkness) and its connection to the city's adoption of the Reformation.

We'll uncover concrete examples of discreet luxury, particularly in book printing and binding, showcasing how opulence persisted in intimate ways despite religious reforms. The podcast will also delve into the challenges of understanding luxury during this period due to limited historical sources.

Finally, we'll draw intriguing comparisons between John Calvin and Girolamo Savonarola, examining the parallels and differences in their attempts to impose moral austerity on their respective cities. This exploration of Geneva's "golden austerity" offers a nuanced view of how the Reformation shaped daily life, culture, and consumption in one of the most influential cities of the time.

Listen to the episode

If you prefer another audio platform (Spotify, Podcast Addict, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Overcast...), click here!

Script

Speaker #0 - Welcome back, everyone. We're diving into a really fascinating topic today. It's 16th century Geneva, right after the Protestant Reformation. So a city kind of redefining itself. And I think we tend to picture this era as super austere, like very strict. But what if I told you that luxury, well, it wasn't entirely absent.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, it's a great point. I mean, the idea that luxury just disappeared after the Reformation, it's a common misconception.

Speaker #0 - Right. And that's exactly what we're going to explore in this deep dive.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. We're going to be looking at a really interesting article by Christophe Chazalon. It's called "Le luxe selon la loi au XVIe siècles: Post Tenebras Lux(e). And it really challenges those assumptions about luxury in post-Reformation Geneva.

Speaker #0 - It sounds like we're in for some surprises. Now, when we think about this period, John Calvin and his doctrines immediately come to mind. Right. So did he basically like single-handedly impose this culture of austerity on Geneva?

Speaker #1 - Well, it's not quite that simple. I mean, Calvin definitely advocated for a simpler life, moderation. But to say that he was like the architect of every single restriction, well, that's a bit of an oversimplification.

Speaker #0 - So it's more nuanced than just saying "Calvin equals austerity".

Speaker #1 - Much more. For example, those sumptuary laws that everyone associates with Calvin, they weren't even his invention.

Speaker #0 - Sumptuary laws being those rules about spending and consumption, like what you could wear, what kind of parties you could throw.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And these laws weren't unique to Geneva either. They existed all over Europe. long before the Reformation.

Speaker #0 - So Calvin was sort of part of a broader trend then, not the sole author of these restrictions.

Speaker #1 - Right. And historian Corinne Walker really debunks this myth in her research. She points out that, and I'm quoting here: "the historiography of Geneva readily claims that Genevan's sumptuary legislation owes everything to Calvin."

Speaker #0 - Interesting. So it seems like giving him all the credit for Geneva's austerity is kind of a historical shortcut.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. It's a good story, but it doesn't really capture the whole picture.

Speaker #0 - Right. It's rarely that straightforward. Okay. So if Calvin wasn't the mastermind behind these sanctuary laws, where did they come from?

Speaker #1 - Well, Geneva had a long and complicated legal history, influenced by his relationships with the Duke of Savoy and the Holy Roman Empire.

Speaker #0 - So these laws were kind of layered over time.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. They evolved over centuries. They reflect different influences. And to really graft the spirit of change in Geneva, let's shift gears for a moment and look at something else: the city's motto.

Speaker #0 - Ooh, mottos. Always intriguing. What was Geneva's motto? And what does it tell us about this period?

Speaker #1 - Well, you've probably heard it Post Tenebras Lux, "After darkness, light".

Speaker #0 - Yeah, it's pretty famous.

Speaker #1 - Right. But it wasn't always so succinct.

Speaker #0 - There's more to the motto. Now this is getting really interesting.

Speaker #1 - The original motto was taken from the Book of Job. It was "Post Tenebras Lux, Spero Lucem", "After darkness, I hope for light".

Speaker #0 - Ah, so there's an element of hope there, which makes sense given all the turmoil of the time.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. It reflects a city yearning for a brighter future.

Speaker #0 - So when did it change to just light?

Speaker #1 - Around 1542, right when Geneva officially adopted the Reformation.

Speaker #0 - Wow, so they dropped the hoping part.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, it's like they were declaring the light has arrived.

Speaker #0 - That's such a powerful statement. And it's interesting because this shift coincided with the minting of those "écus soleil" gold coins, the ones with the... radiant sun.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, exactly. It's almost like they were embodying that motto in their currency.

Speaker #0 - I've also heard this story about Calvin and the motto. Something about him shortening it.

Speaker #1 - Oh, yeah. That's a popular one. The idea that Calvin, the great Latinist, personally edited the motto.

Speaker #0 - Right. It kind of fits the narrative.

Speaker #1 - It does, but it's not actually true.

Speaker #0 - So another historical shortcut.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. We love to simplify things, but history is rarely that neat and tidy.

Speaker #0 - Okay. Well, let's get back to these sumptuary laws. What exactly were they trying to control, and were they effective?

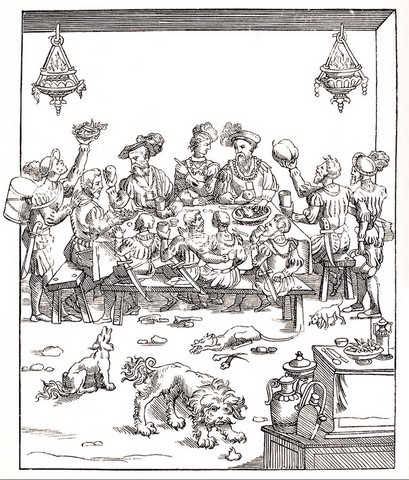

Speaker #1 - So their primary targets were clothing and banquets, the two areas where people could really flaunt their wealth.

Speaker #0 - Makes sense. So no more extravagant gowns or lavish fees.

Speaker #1 - Well, it wasn't quite that extreme. The goal was to curb excess, promote a more moderate, pious lifestyle.

Speaker #0 - So even the wealthiest merchants had to adhere to these standards?

Speaker #1 - In theory, yes. And what's interesting is that Geneva's sumptuary laws were actually less rigid than those in other parts of Europe.

Speaker #0 - Really? How so?

Speaker #1 - Well, unlike some laws that dictated specific attire based on your social class, Geneva's laws applied to everyone, regardless of status.

Speaker #0 - So even the wealthiest merchants had to follow the same rules. That's... That's fascinating. But this shift towards subtlety must make it really hard to study luxury in this period.

Speaker #1 - Right. Absolutely. Unlike earlier periods where we have grand architecture. Elaborate artwork, lavish tombs, post-Reformation Geneva presents a unique challenge.

Speaker #0 - Right, because the Reformation really discouraged ornate religious imagery. And extravagance in church decorations.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. It's not that luxury vanished, but it definitely adapted.

Speaker #0 - In a kind of way, underground.

Speaker #1 - In a way, yes. Traditional forms of artistic patronage, paintings, sculpture, even grand architecture became much more muted.

Speaker #0 - So how do we even know luxury still existed? Are there any clues hidden within this seemingly austere society?

Speaker #1 - There are. And they paint a really fascinating picture of how people navigated this new social and religious landscape. For example, we know of a merchant named Jean Binod. whose wealth in 1539 was estimated at a staggering 3,000 écus.

Speaker #0 - Okay, that definitely sounds like someone who enjoyed a certain level of luxury. But if it wasn't expressed in grand displays, how was this wealth being used?

Speaker #1 - That's the question, isn't it? And it suggests that luxury was taking on subtler forms. For example, we have records of Jean-Francois Ramel spending a significant sum, 20 écus soleil, on a Turkish carpet in 1558.

Speaker #0 - So people were still acquiring luxury items. But maybe being more discreet about it, enjoying them in the privacy of their homes rather than flaunting them in public.

Speaker #1 - Precisely. It's a fascinating shift from outward displays of opulence to a more private enjoyment of luxury. And it makes you wonder how people were expressing their tastes and finding beauty in this new environment.

Speaker #0 - Right. Because that desire for beauty and craftsmanship doesn't just disappear overnight, does it? So where does it go? Did it find new outlets?

Speaker #1 - It most certainly did. And one of the most intriguing examples lies in the world of bookbinding.

Speaker #0 - Bookbinding? Really? That doesn't immediately scream luxury to me.

Speaker #1 - I know it might seem surprising, but think about it. In a time when book illustrations were limited, the binding itself became a way to express individuality and taste. While the contents might be austere, the cover could be a work of art.

Speaker #0 - Like a secret code for the bibliophiles. So these weren't just functional bindings, they were expressions of personal style, and perhaps even a way to discreetly signal wealth.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And we have some amazing examples of these luxurious bindings. There's this 1564 Salter with a stunning red Morocco binding featuring intricate designs and those curious figures called "grotesques".

Speaker #0 - It's like I can just picture it. It sounds absolutely beautiful. And those details must have been incredibly painstaking to create.

Speaker #1 - Oh, absolutely. And then there's the legendary Bible of Henri IV printed in 1588. Imagine a lavish red Morocco binding adorned with a medallion bearing the French royal arms.

Speaker #0 - A royal Bible fit for a king. It sounds like a masterpiece of book binding. Was it commissioned by the king himself?

Speaker #1 - It was intended as a gift for Henry IV, but it was never actually delivered.

Speaker #0 - Why not? What happened?

Speaker #1 - Well, the story goes that Henry IV had converted to Catholicism by then, so the Genevan ambassadors decided to keep the Bible for themselves.

Speaker #0 - Wow. What a twist. So even in a society that supposedly rejected extravagance, we see glimpses of luxury persisting in these intricate, almost hidden ways. It's becoming clear that post-Reformation Geneva wasn't quite the black and white picture we often imagine.

Speaker #1 - You're absolutely right. The absence of those grand artistic displays doesn't equal the absence of luxury. It simply took on different forms, often more intimate and personal. And to fully grasp this shift, we need to delve into how historians like Christophe Chazalon are approaching this unique challenge of studying luxury in this era.

Speaker #0 - All right, so let's unpack that. How do historians even begin to study luxury when it's hidden in plain sight?

Speaker #1 - It's a great question, and one that requires us to rethink our assumptions about what luxury actually means.

Speaker #0 - I'm all ears. Let's dive in.

Speaker #1 - All right. Let's do it.

Speaker #0 - Okay. So let's talk about how historians are actually studying luxury in this period. Because you mentioned it's particularly challenging. What makes it so difficult?

Speaker #1 - Well, as Chazalon points out in his article, historians often have to rely heavily on administrative records and legal documents.

Speaker #0 - Like those sumptuary laws.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And while those sources are definitely valuable, they don't always capture the nuances of daily life.

Speaker #0 - It's like trying to understand modern dating. Based solely on those like relationship advice articles, you might get some helpful tips, but you're missing the real life experiences.

Speaker #1 - That's a great analogy. And that's especially true with something like luxury, which is so tied to personal taste, social dynamics, all those unspoken cultural codes that don't always make it into official documents.

Speaker #0 - So while the laws might tell us about the ideal of moderation, they don't necessarily reveal how people are actually expressing themselves.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And here's where Chazalon makes a really interesting observation. He argues that by striving to make Geneva a city dedicated to God, Calvin might have inadvertently stifled certain forms of cultural expression.

Speaker #0 - You're talking about the decline in painting, sculpture, grand architecture.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And the irony is that those are often the very sources that historians rely on to understand luxury in other historical contexts. Like think about the Renaissance. We glean so much about their values and aspirations through their art and architecture.

Speaker #0 - So in a way, Calvin unintentionally made it even harder for us to understand how luxury was experienced in post-Reformation Geneva.

Speaker #1 - It's a fascinating paradox. By suppressing some of the more outward expressions of luxury, he might have inadvertently encouraged its evolution into more subtle private forms. It makes you wonder if we would even be having this conversation about bookbindings if those other outlets hadn't been muted.

Speaker #0 - But such an interesting thought is like the very scarcity of evidence makes this whole topic even more intriguing.

Speaker #1 - Right. It challenges us to think differently, to read between the lines, to piece together a more nuanced understanding of the past.

Speaker #0 - Which is exactly what makes these deep dives so rewarding. It's not just about learning facts. It's about challenging our assumptions.

Speaker #1 - Absolutely. It's about appreciating that the absence of something doesn't necessarily mean it never existed.

Speaker #0 - Okay. So if we can't rely solely on those traditional sources, how do we approach this challenge? How do we define luxury in this context?

Speaker #1 - Well, that's where we need to broaden our perspective. I think luxury isn't just about lavish spending or ostentatious displays.

Speaker #0 - So if it's not just about the price tag. What else defines luxury? What were people seeking out in post-reformation Geneva?

Speaker #1 - Think about craftsmanship, beauty, rarity, the story behind an object. Those book bindings we talked about, they weren't just expensive. They were works of art reflecting a deep appreciation for detail, a love of beautiful objects.

Speaker #0 - And they served a very practical purpose too. Protecting those precious. books. It's like a fusion of beauty and functionality.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. It's a perfect example of how luxury can be both aesthetically pleasing and purposeful. And in a society where outward displays of wealth were discouraged, these subtle details became even more significant.

Speaker #0 - It sounds like people were finding ways to infuse beauty and meaning into their lives, even within these constraints.

Speaker #1 - Precisely. And this desire for personal expression, for surrounding oneself with things that are well-made and beautiful, is something that transcends time and place.

Speaker #0 - It makes you wonder if we've lost some of that appreciation for craftsmanship in our modern world of mass production.

Speaker #1 - That's a really interesting point. Maybe this deep dive into 16th century Geneva can help us be more aware of those subtle forms of luxury that surround us today.

Speaker #0 - Right. We might not have ornate book bindings everywhere. But maybe there's a beautifully crafted piece of furniture in your home. Or a handmade piece of clothing that you cherish.

Speaker #1 - Or even a simple well-made tool that brings you joy to use. Luxury can be found in the everyday if we know where to look.

Speaker #0 - It's about slowing down and appreciating the quality and thoughtfulness behind the objects we choose to surround ourselves with. Recognizing that luxury doesn't have to be ostentatious or about showing off.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. It can be something deeply personal and meaningful.

Speaker #0 - And it's fascinating to see how this played out in post-Reformation Geneva, where those more traditional avenues for expressing luxury were muted. People found new ways to satisfy that desire for beauty, for craftsmanship. for something that elevates the everyday.

Speaker #1 - It's a reminder that human nature is incredibly resilient and adaptable, even in times of great change. That desire for beauty and self-expression finds a way to persist.

Speaker #0 - But before we get too philosophical, we should probably circle back to those sumptuary laws and how they fit into this whole conversation about luxury.

Speaker #1 - You're right, it's easy to get caught up in the big picture. But those laws are important. They provide crucial context for understanding how luxury was perceived and regulated in this period. They offer a window into the anxieties and values of that society.

Speaker #0 - So were these laws primarily about suppressing luxury altogether, or were they more about redirecting it, encouraging people to express it in different ways?

Speaker #1 - That's a complex question, and there's no easy answer. But what's interesting is that these laws focused mainly on those public displays of wealth. You know, it was about curbing extravagance in areas that were visible to the community, like clothing and banquets.

Speaker #0 - So there was a concern about maintaining social harmony, avoiding those stark displays of inequality that could lead to resentment or envy.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And this ties back to the broader religious context of the Reformation, the emphasis on humility and simplicity, a rejection of worldly excess. Those sumptuary laws, in a way, reflected those values.

Speaker #0 - But as we've seen, that didn't mean people weren't enjoying the finer things in life. It's just that luxury took on a more discreet personal form.

Speaker #1 - Precisely. And this is where those seemingly ordinary objects like book bindings become so significant, they tell a story about how people were navigating this new social and religious landscape, finding ways to express their taste and individuality within those constraints.

Speaker #0 - It makes you wonder if those sumptuary laws and trying to suppress certain forms of luxury might have actually fueled the creativity and ingenuity that led to these new subtler expressions.

Speaker #1 - It's like that saying, necessity is the mother of invention. Right. As restrictions tighten, people find new and often unexpected ways to express themselves.

Speaker #0 - And it highlights the limitations of relying solely on those laws to understand how people were actually living their lives.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. Which brings us back to the importance of Chazalon's research and his call for a more nuanced approach to studying luxury in this period.

Speaker #0 - Okay, so let's dive into that. What are some of the alternative approaches or sources that Chazalon suggests we consider? What kind of clues might help us piece together a more complete picture of luxury in post-Reformation Geneva? So where do we look? If not just those official records, what other sources might reveal those hidden traces of luxury?

Speaker #1 - Well, Chazalon suggests digging deeper into more personal sources. Like correspondence diaries, household inventories, you know those everyday glimpses into people's lives?

Speaker #0 - Ah, so we're looking for those little details, those hints about their tastes and habits.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. Imagine finding a merchant's letter, mentioning a new tapestry he just acquired, or a woman's diary entry describing the fabric she's chosen for a new gown.

Speaker #0 - It's like we're piecing together a puzzle, using these scattered fragments of everyday life.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, it's like being a historical detective. And these seemingly mundane details can be incredibly revealing. For example, imagine finding an inventory that lists a set of fine silverware or a collection of imported spices.

Speaker #0 - Right. It's not just about the big flashy items. It's about those little touches that speak to a desire for quality and refinement.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And through those details, we can start to understand how people were incorporating luxury into their homes, their wardrobes, their social gatherings. even their religious practices.

Speaker #0 - It makes you wonder if those sumptuary laws in trying to regulate those public displays might have inadvertently shifted the focus inward, encouraging people to express their taste and refinement in more subtle, personal ways.

Speaker #1 - It's a fascinating thought, like, maybe those restrictions actually sparked a new kind of creativity.

Speaker #0 - Right, it's like they created a whole new playing field for luxury.

Speaker #1 - Exactly, where discernment and good taste became even more prized. Imagine those dinner parties where the food might have been simple. But the table was set with exquisite linens and the conversation sparkled with wit and erudition.

Speaker #0 - It's like a secret society of tastemakers, signaling their refinement to those who knew how to look for it.

Speaker #1 - That's a great way to put it. And that brings us back to what makes this whole topic so relevant today. Right.

Speaker #0 - Because it challenges us to rethink our own assumptions about luxury.

Speaker #1 - Absolutely. Luxury isn't always about the price tag or the brand name. It can be about the quality of craftsmanship, the story behind an object, the thoughtfulness with which something is created or chosen.

Speaker #0 - It's about appreciating those things that elevate our everyday experiences, whether it's a beautifully bound book, a handcrafted piece of furniture, or even a simple well-prepared meal shared with loved ones.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. Luxury can be found in the everyday if we know how to look for it.

Speaker #0 - And sometimes those subtlest expressions are the most meaningful ones.

Speaker #1 - Well said. It's like those hidden gems that reveal their true beauty when you take the time to really appreciate them.

Speaker #0 - And on that note, I think we've reached the end of our deep dive into luxury in post-Reformation Geneva.

Speaker #1 - I hope our listeners will continue to explore these ideas and maybe even challenge their own perceptions of luxury in their own lives.

Speaker #0 - It's been a fascinating journey. Thanks for joining us as we explore this unexpected world of luxury in a society seemingly defined by austerity. Until next time, keep questioning, keep exploring, and keep diving deep.

Sources

The main source for this episode is our article “Le luxe selon la loi au XVIe siècle: Post Tenebras Lux(e)”, published in the catalog of the exhibition “Post Tenebras Luxe”, curated by Donatella Bernardi for the Musées d'Art et d'Histoire de Genève, in 2009. You can read it on our personal website by clicking HERE (in French).

Here is a brief summary of the article's content:

The text begins by emphasizing that inferring lived reality from legislation is unreliable, as many regulations remain unenforced. Instead, one must seek the underlying meaning of the rules, acknowledging that legislation aims to influence practices by confirming, correcting, or prohibiting them. Just as Rome has Romulus and Remus, Geneva has Calvin, elevated to mythical status by historians and biographers. The article examines the adoption of Geneva's motto, "Post Tenebras Lux" (After Darkness, Light), and the role Calvin may have played in its religious significance.

Initially, the motto "Post tenebras spero lucem" (After darkness, I hope for light) was adopted around 1530, drawn from the Book of Job, reflecting the uncertain political climate. It appeared on seals and official documents. Following the adoption of the Reformation in 1536, and Calvin's return in 1541, the motto was modified to "Post Tenebras Lux" and linked to the trigram IHS within a sun, symbolizing the adoption of the Reformation and a shift from a political to a religious meaning.

The text then questions Calvin's actual influence on Genevan life, noting that sumptuary laws existed throughout Europe since the 12th-13th centuries and that Calvin himself was skeptical about regulating expenses. It highlights that Calvin's main contribution was giving Geneva international renown as a major religious center, not necessarily imposing strict austerity. The concept of Geneva as the "Protestant Rome" represents an idealized city living according to the Gospel, though the reality was more complex.

The article draws parallels between Calvin and Savonarola, who imposed austerity on Florence. Both figures illustrate attempts to reform cities morally, with Savonarola's actions ultimately leading to his downfall. Calvin, in contrast, authorized reasonable interest rates and emphasized the moral and spiritual responsibility in economic relationships. Finally, it's noted that Geneva's sumptuary laws regulated expenses on luxury goods, particularly clothing and banquets, and, while often attributed to Calvin, actually reflect broader European trends. Corinne Walker argues that Calvin's opposition to luxury was constant, but he was also aware of the difficulties and relativities involved in regulating expenses.

And much more

To enrich your knowledge of the world of luxury under the Ancien Régime, we suggest the following reading suggestions:

- T. ARTAN, "Aspects of the Ottoman elite's food consumption: looking for "staples", "luxuries", and "delicacies" in a changing century", in Donald QUATAERT, ed., Consumption studies and the history of the Ottoman Empire, 1550-1922, Albany (NY): State University of New York Press, 2000, pp. n/a

- Donatella BERNARDI (ed.), Post Tenebras Luxe, Genève: Labor et Fides, 2009/08, 144 p.

- Christopher J. BERRY, "The history of ideas on luxury in the Early Modern Period", in Pierre-Yves DONZÉ / Véronique POUILLARD / Joanne ROBERTS (eds.), The Oxford handbook of luxury business, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020/11, pp. 21-40 (web)

- Caroline BLECH BAUER, Travail et responsabilité selon Jean Calvin, une interprétation par le devoir de lieutenance, Strabourg: Université de Strasbourg / Genève: Université de Genève, 2015, 264 p.: thèse de doctorat (web)

- Vincent CHENAL / Frédéric HUEBER, Histoire des collections à Genève du XVIe au XIXe siècle, Genève: Georg, 2011, 280 p.

- Jean-Marie CONSTANT, La noblesse en liberté (XVIe - XVIIe siècles), Rennes (FR): Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2004, 302 p.: in particular chap. 5, entitled "Noblesse et élite au XVIe siècle: les problèmes de l'identité double", pp. 67-80 (web)

- Matthias FREUDENBERG, "Economic and social ethics in the work of John Calvin", HTS theological studies (Pretoria), vol. 65, n° 1, 2009/01, [7 p.] , online (web)

- Johanna ILMAJUNNAS / Jon STOBART (eds.), A taste for luxury in Early Modern Europe. Display, acquisition and boundaries, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017/06, 315 p.

- Kathleen M. LLEWELLYN, "A fantastic frenzy of consumption in Early Modern France", Renaissance and Reformation, vol. 38, n° 3 special issue: Les passions et leurs enjeux au seizième siècle, 2015/06-08,, pp. 119-139 (web)

- Sara MAZA, "Luxury, morality, and social change: why there was no middel-class consciousness in prerevolutionary France", The journal of modern history, vol. 69, n° 2, 1997/06, pp. 199-229 (web)

- Kenneth POMERANZ, The great divergence: China, Europe, and the making of the modern world economy, Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 2000, 392 p.: in particular chap. 3, entitled "Luxury consumption and the rise of capitalism", pp. 114-165 (web)

- Daniel ROCHE, La culture des apparences. Une histoire du vêtement (XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles), Paris: Fayard, 1989, 549 p.

- Otto SCHAEFER, "Théâtre de la gloire de Dieu et Droit usage des biens terrestres: Calvin, le calvinisme et la nature", in Jacques VARET (ed.), Calvin, naissance d'une pensée, Tours (FR): Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 2012, pp. 213-226 (web)

- John SLAMSON, "The first book of fashion: the first sartorialist of the 16th-century", parisiangentleman.com, 2016/05/25, online (web)

- Marianne STUBENVOLL, "Niveaux et répartition des fortunes dans les pays de Vaud, Gex, Ternier-Gaillard et Thonon en 1550", Revue historique vaudoise, n° 102, 1994, pp. 43-87 (web)

- Corinne WALKER, Une histoire du luxe à Genève. Richesse et art de vivre aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, Chêne-Bourg (GE): La Baconnière, 2018/12, 264 p.

RCnum PROJECT

This historical popularization podcast is developed as part of the interdisciplinary project entitled "A semantic and multilingual online edition of the Registers of the Council of Geneva / 1545-1550" (RCnum) and developed by the University of Geneva (UNIGE), as part of funding from the Swiss National Scientific Research Fund (SNSF). For more information: https://www.unige.ch/registresconseilge/en.