SPECIAL GUESTS // Stepchildren of the Reformation: Calvin's Family Drama

A brief summary

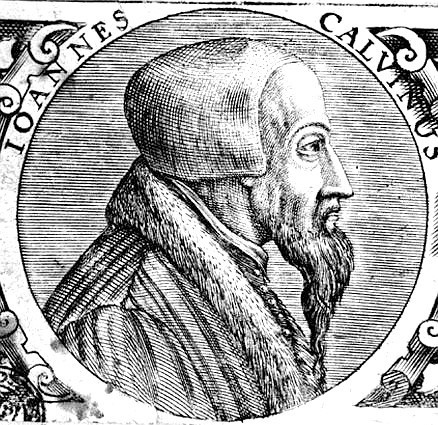

Welcome to "Really Calvin, is this an ideal life? A historical podcast." Today, we're delighted to bring you an episode created by our special guests, Isabella Watt and Professor Jeffrey R. Watt, who are the editors of the "Registers of the Consistory of Geneva in the Time of Calvin". They invite us to dive into the juicy family drama of 16th-century Geneva, where even the great reformer John Calvin couldn't escape domestic turmoil.

Picture this: Calvin, the stern moralist, suddenly finds himself playing stepdad to two rebellious teenagers. That's right, folks! When Calvin married Idelette de Bure in 1540, he inherited her children from a previous marriage: Jacob and Judith Tourneur. Talk about an instant family!

Now, you might think Calvin's home would be a model of Protestant virtue, but oh boy, were these kids determined to test his patience. Judith, it seems, had a taste for scandal, getting caught up in an adulterous affair that set Geneva's gossip mill abuzz. Meanwhile, Jacob was busy living it up as Geneva's bad boy, his dissolute behavior making Calvin's hair even grayer than usual.

But here's where it gets really interesting. Calvin, the man who helped establish Geneva's strict moral code, now had to watch as his own stepchildren were hauled before the Consistory - the very court he helped create to enforce godly behavior. Talk about awkward family dinners!

Join us as we uncover how Calvin navigated this family crisis, balancing his roles as reformer, civic leader, and stepfather. Did he pull strings to protect his wayward stepchildren? Or did he let the full force of Geneva's moral law fall upon them? Tune in to find out how Calvin put his own house in order - or tried to - in this episode of "Really Calvin, is this an ideal life?"

Listen to the Episode

If you prefer another audio platform (Spotify, Podcast Addict, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Overcast...), click here!

Script

Speaker #0 - Welcome back, everyone. Today, we're going deep into 16th century Geneva. We've got a whole bunch of sources, like legal documents, court records, and some historical analyses. It's all about Judith Tourneur, John Calvin's stepdaughter. And it's really like a time capsule, religious and social upheaval.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, it's fascinating to think about because Geneva at the time was obsessed with morality.

Speaker #0 - Totally.

Speaker #1 - And all under Calvin's, you know, watchful eye.

Speaker #0 - Right. Right.

Speaker #1 - And Judith, well, she ends up kind of in the center of this scandal. That rocks the city.

Speaker #0 - So before we get into all the juicy details, can you remind us who John Calvin was and why he was such a big deal in Geneva?

Speaker #1 - Oh, of course. So John Calvin was this incredibly influential Protestant reformer. He's the guy who believed in predestination, meaning God had already chosen who would be saved and who wouldn't. And he established a really, really strict moral code for the city of Geneva covering everything. Everything from church attendance to clothing, even dancing.

Speaker #0 - So not really the party town.

Speaker #1 - Not really, no. Not the place to go for a good time. Calvin saw Geneva as this kind of model city, this shining example of godly living. And to enforce those moral standards, he established the consistory.

Speaker #0 - The consistory. What was that?

Speaker #1 - So think of it as this morals court, made up of church elders and city officials. They had the power to investigate and punish anyone who stepped out of line.

Speaker #0 - Got it. So high stakes for good behavior.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, absolutely.

Speaker #0 - Now where does Judith fit into all of this?

Speaker #1 - Well, Judith's mother, Idelette de Bure, she was a widow with two children when she married Calvin. Her son, Jacob, and of course, Judith.

Speaker #0 - Okay. And what about Judith's biological father? Feels like there's a but coming.

Speaker #1 - There is a but. Her father was Jean Stordeur, an anabaptist, and this is crucial because anabaptists were kind of like the rebels of the Reformation. They believed in adult baptism separation of church and state, and some even advocated for pacifism. Calvin, on the other hand, strongly opposed their beliefs. He saw them as a threat to his vision for Geneva.

Speaker #0 - I see. So Judith is growing up in this incredibly tense environment caught between her father's beliefs and her stepfather's incredibly powerful position. Talk about family drama.

Speaker #1 - Right. It's a recipe for conflict, for sure. And that conflict kind of comes to a head in 1562 when Judith is a married woman. She's accused of adultery with Étienne Gemaux.

Speaker #0 - Étienne Gemaux?

Speaker #1 - A journeyman working for her husband. And this is where things get really interesting.

Speaker #0 - Okay. So first... what exactly was a journeyman?

Speaker #1 - Oh, so a journeyman was like an apprentice, a skilled worker learning their trade. They often traveled from town to town working for different masters. So Etienne was basically like a live-in employee in Judith's household.

Speaker #0 - Okay, I see. And adultery. That was a pretty big deal in Calvin's Geneva, right?

Speaker #1 - Huge. Like I said, Geneva was supposed to be this model of morality. Adultery threatened the very fabric of their society. It was sin against God, you know, a violation of marriage vows a disruption of social order.

Speaker #0 - So what happened? Did Judith deny the accusations?

Speaker #1 - So the records we have from the criminal investigation are really detailed. They show that Judith initially confessed to the affair. But then she retracted her confession.

Speaker #0 - She did.

Speaker #1 - Saying she only admitted it out of fear of torture.

Speaker #0 - Oh, wow.

Speaker #1 - I mean, can you imagine?

Speaker #0 - Yeah, that's like...

Speaker #1 - What pressure she must have been under.

Speaker #0 - That's terrifying.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, and torture was a very real threat back then.

Speaker #0 - Of course. Yeah!

Speaker #1 - But she eventually confesses again.

Speaker #0 - She does.

Speaker #1 - She does, and the details, the details are something else. They mentioned encounters in the kitchen even the maid's bed.

Speaker #0 - Oh my gosh!

Speaker #1 - Judith also apparently showered at ten, with gifts, like two handkerchiefs.

Speaker #0 - Two handkerchiefs? Wow!

Speaker #1 - It seems like everyone in the household had an opinion on the matter.

Speaker #0 - Except it seems the maid herself. Why do you think she never testified?

Speaker #1 - That's a good question. It's possible she was pressured to stay silent. Or maybe she was afraid of, you know, the repercussions of speaking out. I mean, this is a society where reputation was everything. Or maybe she genuinely didn't know what was going on. The sources don't really tell us. It's one of those historical mysteries that just keeps us guessing.

Speaker #0 - It's so interesting to think about, like, the untold stories. All the whispers and the secrets hidden within the official records. So what happened next? What was the verdict? So we've got this scandal, you know, unfolding in a city where morality is practically a religion. What happened to Judith and Etienne? Did Calvin, like, step in and smite them with a lightning bolt or something?

Speaker #1 - Well, no lightning bolts.

Speaker #0 - Okay.

Speaker #1 - But they were definitely punished. Both Judith and Etienne were publicly caned.

Speaker #0 - Publicly caned?

Speaker #1 - Through the streets of Geneva.

Speaker #0 - Oh, wow! Public shaming? I bet that was effective, for deterring future?

Speaker #1 - I would think so.

Speaker #0 - Indiscretions. Was that a typical punishment for adultery, though?

Speaker #1 - It was. Remember those criminal investigation records? Well, those allow us to compare Judith and Etienne's sentence to other adultery cases in Geneva, and it seems that public caning, sometimes with fines, was kind of the go-to punishment.

Speaker #0 - Okay, so their punishment fit the pattern, but then the sources mention that Etienne was also banished for life.

Speaker #1 - Right.

Speaker #0 - That seems a little harsh.

Speaker #1 - It does seem a bit harsh, yeah, on top of the caning. The banishment wasn't solely because of the adultery. It turns out that Etienne had also failed to register as a resident of Geneva. And the city was incredibly strict about controlling, you know, who lived within its walls. especially after 1555, when Calvin's authority was really solidified. Foreigners were viewed with a lot of suspicion, and unregistered residents could be seen as a threat to the social order.

Speaker #0 - So, Etienne's actions had consequences kind of beyond just the affair. You couldn't just waltz into Geneva and start canoodling with the reformer's stepdaughter without facing the music.

Speaker #1 - Precisely.

Speaker #0 - Got it.

Speaker #1 - Now, amid all this chaos, there's another layer we need to consider: divorce.

Speaker #0 - Right. Divorce.

Speaker #1 - This is 16th century Geneva, deeply shaped by Calvin's reforms, where divorce was not exactly commonplace.

Speaker #0 - Right! And the consistory comes into play here, right? They were like the morality police of Geneva.

Speaker #1 - Well, not exactly police, but they were certainly the guardians of morality. Their job was to investigate these moral transgressions, promote reconciliation and ultimately reintegrate sinners back into the community.

Speaker #0 - So what did they have to say about Judith's adultery? Did they like throw the book at her?

Speaker #1 - Surprisingly, no, they didn't directly address her adultery.

Speaker #0 - They didn't?

Speaker #1 - No. Instead, they sent a delegation to her house, to inform her that she was barred from communion.

Speaker #0 - Oh, wow.

Speaker #1 - This is a pretty unique occurrence.

Speaker #0 - It was.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. Something we don't really see in other adultery cases from the records.

Speaker #0 - Hold on. So the consistory could publicly punish people for things like dancing and card playing, but they chose to handle Judith's adultery. A pretty major sin behind closed doors. That seems...

Speaker #1 - It does seem odd, particularly because the consistory usually emphasized reconciliation between couples, even in cases of adultery. So this makes you wonder if Judith received some special consideration, because of her connection to Calvin.

Speaker #0 - Almost like they were trying to sweep the whole messy affair under the rug to protect Calvin's reputation.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. Condemning the reformer's stepdaughter publicly would have been a massive scandal. Imagine all the whispers and the gossip that would have gone through Geneva. It's possible they were just trying to contain the fallout by handling her case more privately.

Speaker #0 - Yeah. Okay, so we've got adultery, public caning banishment, and whispers of special treatment. What about Judith's husband? How did he react to all of this?

Speaker #1 - Well, let's just say he didn't stick around to forgive and forget.

Speaker #0 - Oh, okay.

Speaker #1 - Leonard Du Mazel, Judith's husband, he applied for and was granted a divorce.

Speaker #0 - Okay. Was divorce easy to obtain in Geneva?

Speaker #1 - Not really. The consistory, like I mentioned before, they usually emphasize reconciliation, and often they would really drag out the process, urging couples to work things out. But in Judith's case, they were unusually quick to grant the divorce.

Speaker #0 - Interesting. So not only was her adultery case handled differently, but her divorce also seemed to have been fast-tracked. Does that add more fuel to the special treatment theory?

Speaker #1 - It does. But let's not jump to conclusions just yet. We have to remember that the sources we have, offer a limited perspective, right? We can't get inside the heads of those consistory members, right? Maybe they genuinely believed that Leonard's insistence on divorce was justified, and just on no point in prolonging the proceedings

Speaker #0 - It's hard not to see Calvin's influence kind of lurking in the background here. He was the most powerful figure in Geneva. It's not unreasonable to think that his presence kind of cast a shadow over these proceedings.

Speaker #1 - I agree the power dynamics at play were significant, and it would be naive to dismiss them entirely.

Speaker #0 - Yeah, for sure. Speaking of power dynamics, Judith's brother Jacob also had his own run in with the consistory, didn't he?

Speaker #1 - He did.

Speaker #0 - Okay.

Speaker #1 - The sources tell us that he was summoned for attending mass, and living what they called a dissolute life.

Speaker #0 - Okay. So a bit of a rebel.

Speaker #1 - Yeah. Sounds like it.

Speaker #0 - Just like his biological father, attending mass, though, seems pretty harmless compared to adultery.

Speaker #1 - It might seem that way to us, but in Calvin's Geneva, attending mass was a direct challenge to the established religious order. Remember, Calvin wanted to create this model Protestant city, and Catholic practices were seen as a threat to that vision.

Speaker #0 - OK, so context is key here. What about this dissolute life? What did they even mean by that?

Speaker #1 - Well, this speaks to a broader anxiety in Geneva at the time. This fear of idleness and profligacy, especially among young men. They worried about unemployment, gambling, drinking, basically any behavior that didn't fit their idea of productive God-fearing citizens.

Speaker #0 - So it sounds like they were really trying to control every aspect of people's lives.

Speaker #1 - Yeah, they were. So what was Jacob's punishment? Did he get off lightly compared to his sister? He was initially barred from communion, just like Judith, and he even spent a few days in jail.

Speaker #0 - Oh, wow.

Speaker #1 - But remember, the consistory's ultimate aim was to reintegrate sinners back into the community. They emphasize repentance and reconciliation.

Speaker #0 - So what happened to Judith and Jacob in the aftermath of all of these scandals? Did they become social outcasts?

Speaker #1 - So last time we were talking about Judith and Jacob, you know, and how they were both punished by the consistory, for their, you know, quote, moral transgressions. What happened to them after that?

Speaker #0 - Well, they didn't just disappear from Genevan society. Remember that consistory's goal was ultimately about redemption. Both Judith and Jacob eventually requested and were granted readmission to communion.

Speaker #1 - That's interesting. So even in a society that was so obsessed with moral purity, there was still a path back for those who strayed. Makes you wonder though, did their connection to Calvin play any role in their reintegration.

Speaker #0 - It's certainly possible. The sources don't explicitly say, you know. But it's hard to ignore the potential influence of his position. Imagine the pressure on the consistory to show leniency towards the reformer's own family.

Speaker #1 - Adds another layer to this whole question of special treatment, doesn't it? Absolutely. And this is one of the things that makes Judith and Jacob's stories so compelling. We can analyze the evidence, compare their punishments to others consider the political climate, but we're still left with some ambiguity.

Speaker #0 - It's like a historical puzzle with a few missing pieces.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And that's the beauty of history. It's not always about finding definitive answers. It's about grappling with those ambiguities, exploring the gray areas, and kind of piecing together a narrative that makes sense of the evidence we have.

Speaker #0 - So even though, we might never know for sure if they received preferential treatment, their stories still offer valuable insights.

Speaker #1 - Absolutely. For one thing, they highlight those complexities of power and influence. We see how personal connections could potentially impact the course of justice, even in a system that's strived to be fair and impartial.

Speaker #0 - It's a reminder that no society, no matter how righteous or well-intentioned, is immune to human failings and biases. And their stories also reveal the power of social norms and expectations. Judith's adultery, Etienne's failure to register as a resident, Jacob's dissolute lifestyle, these were all transgressions against the carefully constructed moral order of Calvin's Geneva.

Speaker #1 - Exactly.

Speaker #0 - It's fascinating to see how these individual stories connect to these larger societal anxieties.

Speaker #1 - It is. And those anxieties, that fear of idleness, the obsession with moral purity, the suspicion of outsiders, they resonate even today, don't they? We might express them differently, but those underlying concerns about social order and control are still very much alive In contemporary society.

Speaker #0 - It's a reminder that the past isn't really that distant after all.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. And speaking of connections to the present, we can't forget the double standard that Judith faced as a woman accused of adultery while both she and Etienne were punished. The sources suggest that women in 16th century Geneva often bore the brunt of societal disapproval and legal consequences.

Speaker #0 - It's a sobering reminder that the fight for gender equality has been a long and often difficult one.

Speaker #1 - It has. And Judith's story, even with its ambiguities, can serve as a starting point for those conversations. It compels us to examine the ways in which gender roles and expectations have shaped our understanding of morality and justice, both historically and in the present day.

Speaker #0 - It's like these 16th century court records. They aren't just dusty relics of the past. They're still relevant, still sparking important discussions centuries later.

Speaker #1 - That's what makes these deep dives so rewarding. We start with these seemingly isolated events and we end up exploring these much broader themes that connect us across time and cultures.

Speaker #0 - So, as we wrap up our deep dive into Judith Tourneur's story, what's the one key takeaway you want our listeners to remember?

Speaker #1 - I think it's this: history is about more than just dates and names. It's about exploring the lives of individuals, understanding their choices, and recognizing how those choices reflect the social, political and religious forces of their time.

Speaker #0 - And sometimes those choices, even the seemingly scandalous ones, can challenge our assumptions, provoke difficult questions and ultimately lead us to a richer, more nuanced understanding of the human experience.

Speaker #1 - Beautifully said.

Speaker #0 - This deep dive has been a wild ride through 16th century Geneva, filled with adultery, intrigue, and glimpses into the complexities of power, morality, and social control.

Speaker #1 - It's been a pleasure exploring those complexities with you.

Speaker #0 - Likewise. And to our listeners, thank you for joining us on this journey. We hope it sparked your curiosity and left you with something to ponder. Until next time, keep exploring, keep questioning, and keep diving deep.

Sources

- Adultery trial: Judith Tournent, Estienne Gemeau, and Leonard Mazel

- Geneva Consistory records: adultery, divorce, and testimony, 1557-1562

- Jacob Stordeur: Calvin's stepson and church discipline

- Jeffrey R. Watt, "Calvin puts his house in order: the reformer confronts his dissolute stepchildren", The Sixteenth Century Journal: the Journal of Early Modern studies, vol. 55, n° 1-2, 2024, pp. 73-91 (web)

And much more...

Here are a few suggestions for further reading on family life in Geneva at the time of Calvin:

- Irena BACKUS, “Women around Calvin: Idelette de Bure and Marie Dentière,” in Christophe STÜCKELBERGER / Reinhold BERNARDT (eds.), Calvin Global: how faith influences societies, Genève: Globalethics.net, 2009, pp. 95-110 (web)

- Charmarie Jenkins BLAISDELL, "Calvin’s letters to women: the courting of ladies in high places", The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 13, n° 3, 1982, pp. 67-84 (web)

- Jules BONNET, "Idelette de Bure: femme de Calvin, 1540-1549", Bulletin de la Société de l'histoire du protestantisme français, n° 4, 1856, pp. 636-646

- Emile Michel BREAKMAN, Idelette de Bure, épouse de Jean Calvin, Paris: Éditions Olivétan, 2009/06, 126 p.

- Susan C. KARANT-NUNN, "John Calvin's sexuality", in Susan C. KARANT-NUNN / Ute LOTZ-HEUMANN (eds.), The cultural history of the Reformations: theories and applications, Wolfenbüttel (DE): Herzog August Bibliothek, 2021, pp. n/a

- Robert M. KINGDON, Adultery and divorce in Calvin's Geneva, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1995/03, 224 p.

- Roderick PHILIPS, "Stepfamilies from a historical perspective", Marriage and family review, vol. 26, n° 1-2, 1997, pp. 5-18 (web)

- Barbara PITKIN, "John Calvin", in John WITTE Jr. / Gary S. HAUK (ed.), Christianity and family law: an introduction, Cambridge (MA): Cambridge University Press, 2017/11, pp. 211-228

- Cornelia SEEGER, Nullité de mariage, divorce et séparation de corps à Genève au temps de Calvin: Fondements doctrinaux, loi et jurisprudence, Lausanne (CH): Société d’histoire de la Suisse romande, 1989, 502 p.

- Lyndan WARNER (ed.), Stepfamilies in Europe, 1400-1800, London / New York: Routledge, 2018, 306 p.

- Jeffrey R. WATT, The Consistory and social discipline, Rochester (NY): University of Rochester Press, 2020, 338 p. (web)

- Jeffrey R. WATT, The making of modern mariage: matrimonial control and the rise of sentiment in Neuchâtel, 1550-1800, Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press, 1993/01, 302 p.

- John WITTE Jr. / Robert M. KINGDON, Sex, marriage, and family life in John Calvin's Geneva (vol. 1): courtship, engagement, and marriage, Grand Rapids (MI): Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2005/10, 545 p.

*******

RCnum PROJECT

This historical popularization podcast is developed as part of the interdisciplinary project entitled "A semantic and multilingual online edition of the Registers of the Council of Geneva / 1545-1550" (RCnum) and developed by the University of Geneva (UNIGE), as part of funding from the Swiss National Scientific Research Fund (SNSF). For more information: https://www.unige.ch/registresconseilge/en.