Genevan Hygiene, 1536-1564

A brief summary

Welcome to "Really Calvin, is this an ideal life? A historical podcast." Today, we're peering into the homes and families of 16th-century Geneva, uncovering a world both familiar and alien to our modern sensibilities. Between 1536 and 1564, Geneva's family structure was deeply patriarchal, with women generally occupying subordinate roles, though exceptions did exist. This wasn't just about social norms; it was a response to the harsh realities of the time.

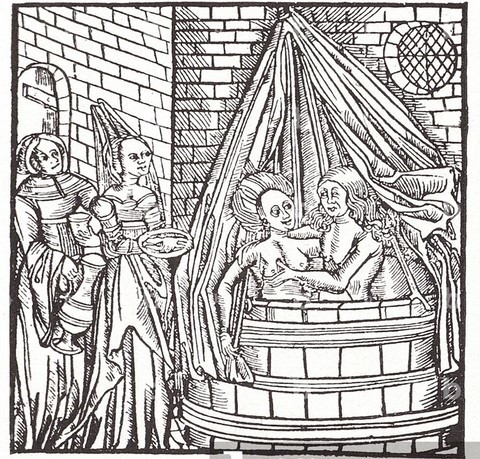

High infant mortality rates and limited hygiene shaped family dynamics and property practices. At the heart of each household stood the patriarch, wielding significant power over family resources and decision-making. Yet, even as Calvin sought to reshape Geneva's morality, some aspects of daily life proved resistant to change. Public baths, for instance, remained sites of potential promiscuity despite Calvin's efforts to regulate them.

Join us as we explore how these family structures and hygiene practices offer a unique window into the complex interplay of tradition, reform, and daily life in Calvin's Geneva.

Listen to the episode

If you prefer another audio platform (Spotify, Podcast Addict, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, Overcast...), click here!

*******

Script

Speaker #0 - All right, let's dive in. Today, we're getting kind of personal talking hygiene.

Speaker #1 - Hygiene.

Speaker #0 - Yeah, but not just like any hygiene. We're going way back, back to 16th century Geneva.

Speaker #1 - Ah, Reformation era, John Calvin and all that.

Speaker #0 - Exactly. We're going to see how they dealt with, well, keeping clean back then, or, you know, maybe not so clean.

Speaker #1 - Fascinating, period. I bet their practices were quite different from ours today.

Speaker #0 - You think? Our main source is a recent paper. It really digs deep into hygiene in Geneva between 1536 and 1564. I think we can handle the nitty gritty.

Speaker #1 - Absolutely. I'm all in. Always interesting to see how these everyday things change over time and how they reflect broader social trends even.

Speaker #0 - Totally. Plus, we'll be connecting this back to some observations from the philosopher Michel Serres. He wrote about life in France before the 1950s. See how things compare, right?

Speaker #1 - Ah, Serres. Excellent choice. He had a knack for those everyday details. Should be a good contrast.

Speaker #0 - Yeah, I'm curious to see those comparisons. And listeners, you might be surprised. How much has changed? Or maybe how much hasn't? Stick with us.

Speaker #1 - One thing that jumps out from the paper is how social structures impacted hygiene. Back then, Geneva was very patriarchal. Head of the household, always a man, controlled all the assets.

Speaker #0 - So like total male dominance, just guys running the show?

Speaker #1 - Well, not just about that. It was a time with a very high death rate. Especially for kids. Imagine losing a child was sadly common. This system where one person controlled everything, it actually helped with inheritance. Made things simpler when, sadly, families were constantly dealing with loss.

Speaker #0 - So it was practical too. Not just about men being in charge.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. But let's get to the heart of it. The hygiene. Daily baths. Not really a thing in 16th century Geneva.

Speaker #0 - No kidding. So no quick dip in Lake Geneva every morning. Why not?

Speaker #1 - Well, the church, for one, they weren't big fans of frequent bathing. And that view kind of stuck around even after the Reformation with Protestants like Calvin.

Speaker #0 - Wait, the church discouraged bathing? That's wild.

Speaker #1 - It's true. Back then, they thought water could mess with your humors, basically like your essential fluids. They thought it could make you sick.

Speaker #0 - Wow. Talk about a different mindset. We're all about germs and daily showers now. But wait, even if they wanted to bathe daily, were there even enough places?

Speaker #1 - Good point. Geneva only had... two or three public bath houses for like 7,000 people and they were called it too. Fancy, right? But not cheap to use. Heating all that water, you know.

Speaker #0 - So not exactly convenient to pop in for a quick wash whenever you felt like it.

Speaker #1 - Nope. Limited access definitely contributed to them not bathing so often.

Speaker #0 - Okay, so no daily baths. What about clothes? Did they at least change those regularly?

Speaker #1 - Not really. Most folks had just one outfit for everyday stuff. Wore it till it was, well, basically falling apart. maybe one extra outfit for special occasions. But that was it. Laundry day wasn't really a thing then.

Speaker #0 - Sounds kind of, well, smelly.

Speaker #1 - Probably. But hey, that reminds me of something Michel Serre wrote about his childhood in France before the 1950s. Not much laundry there either, apparently.

Speaker #0 - Really? So that less than fresh lifestyle, it spans centuries.

Speaker #1 - It's fascinating, right? Not just a 16th century Geneva thing. Seems like it was pretty common in Europe for a long time.

Speaker #0 - Makes you wonder, what finally changed things? When did bathing go from... dangerous to a daily ritual. And how does all this compare to our habits today? Stay tuned, folks. We'll get into that right after this.

Speaker #1 - We will. That Elle magazine study asking if French women were clean. Pretty bold, huh?

Speaker #0 - Yeah. Can you imagine a magazine doing that today? So what made it such a big deal?

Speaker #1 - Well, for one, it got people talking about hygiene. Like, how often do you bathe, change your clothes? Suddenly, everyone was comparing themselves.

Speaker #0 - Like it set a new standard. Yeah. Especially for women, it sounds like.

Speaker #1 - You could say that. And this was right after World War II. Things were changing, new ideas, new technologies. Hygiene was part of that.

Speaker #0 - So it wasn't just the study. It was like a whole shift in thinking.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. People were realizing, hey, maybe hygiene is actually important for health.

Speaker #0 - And did the study, like, give advice, tell people how to be cleaner?

Speaker #1 - It did. Daily baths, hair washing, deodorant, the whole nine yards. It was like a hygiene how-to guide disguised as a study.

Speaker #0 - Wow. So it... Really did kickstart this whole hygiene revolution.

Speaker #1 - It did. By the 1950s, things were changing. The study found that 52% of French women bathed daily in 51. Fast forward to a 2020 study, it's 81%. And for men, it jumped from practically no data to 71% bathing daily.

Speaker #0 - Big change. But going back to Geneva for a sec. If they weren't bathing all the time, how did they deal with, well, body odor?

Speaker #1 - Good question. We gotta remember, what's acceptable changes over time. What we think is stinky now, they might not have even noticed.

Speaker #0 - I guess so. But it must have done something.

Speaker #1 - Right. Oh yeah. Perfume was huge in 16th century Geneva. Herbs, flowers, spices, all mixed up to smell nice. And their clothes, remember, they didn't wash those often, so they'd absorb all those scents.

Speaker #0 - They're like their own kind of deodorant.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. Now, the source mentions Calvin. He tried to control those bathhouses, the "étuves" (ovens).

Speaker #0 - What was he trying to control?

Speaker #1 - Well, as we said, they weren't just for getting clean. They were like social hangouts. People ate there, drank, even spent the night.

Speaker #0 - So like a spa, a restaurant, and a hotel all rolled into one.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. But all that socializing, well, it led to some concerns. Let's just say. Not everyone was there for the hot water. Calvin especially worried about men and women mixing.

Speaker #0 - Oh, trying to keep things morally upright.

Speaker #1 - You could say that. He tried multiple times to separate men and women, but, well, it didn't really work.

Speaker #0 - Sounds like good old human nature won out. Even Calvin's Geneva.

Speaker #1 - It seems so. But this whole thing, the bathhouse, is being for both hygiene and socializing. It's interesting, right? Trying to keep things clean, but also people just want to have fun.

Speaker #0 - They're like that everywhere, right? Parks, libraries, wherever people gather. Rules versus reality.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. So we've seen how those hygiene practices, or lack of them, lasted for ages. And then, boom, things change in the mid-20th century. What's it all mean? What are the big takeaways?

Speaker #0 - Yeah, good question. What have we learned from all this smelly history?

Speaker #1 - Well, number one, our idea of hygiene, it's always changing. What's dirty to one generation is totally normal to another. It's all about context.

Speaker #0 - And science plays a huge role, right? Like, discovering germs changed everything.

Speaker #1 - Absolutely. Germs, antibiotics, hand washing. Imagine it wasn't until the mid-1800s the doctors figured out, hey, maybe we should wash our hands.

Speaker #0 - Crazy, right?

Speaker #1 - It is. Shows how far we've come. But you said earlier, some things we do today, future folks might find weird, right?

Speaker #0 - Oh, definitely. All our antibacterial stuff, for one, future generations, they might wonder why we were so afraid of germs. Maybe they'll know way more about bacteria and how it's not always a bad thing.

Speaker #1 - Like our grandkids might be like, what were they so scared of?

Speaker #0 - Totally. And it's not just bacteria. They might look at all our disposable stuff, the wipes, the paper towels, all that plastic and think we were crazy wasteful.

Speaker #1 - So even though we might think we're super clean now, there's always room for like hygiene 2.0.

Speaker #0 - Exactly. The history of hygiene. It's a good reminder. What's normal is always shifting. And who knows what the future holds?

Speaker #1 - You know, it's weird to think about like washing your hands. It's so basic, but it has this whole crazy history behind it. Right. It really shows you hygiene. It's not just about being clean. It's tied to everything. Social stuff, what we know about science, even how we treat the environment.

Speaker #0 - Before we totally move on, I got asked about something the source mentions. Even some pastors were hanging out at those bathhouses, the etudes. Isn't that a little, I don't know, hypocritical considering the church was against bathing?

Speaker #1 - Yeah. Seems a bit off, doesn't it? But remember, those etudes, they were more than just baths. They were like the spot to be. People went there to chill, eat, drink, gossip.

Speaker #0 - So it wasn't about getting clean for them. It was about the social scene.

Speaker #1 - Probably. But it also shows you there's always this tension between what religion says you should do and what people actually do. The church might have said, bathing is bad, but hey, people still wanted to have fun. Even pastors, I guess.

Speaker #0 - I guess some things never change. Speaker #1 And that brings up something else. We've been saying in Geneva and France before the 50s, people didn't bathe as much. But does that mean they were actually dirtier?

Speaker #0 - Yeah, good point. It's easy to judge looking back. But is that fair?

Speaker #1 - I don't think so. They just did things differently. It was normal for them.

Speaker #0 - And they had their own ways of dealing with things, right? Like perfume, you said.

Speaker #1 - Exactly. Maybe not squeaky clean by our standards, but not like living in filth either.

Speaker #0 - Right. They figured out what worked for them. So as we wrap up our hygiene deep dive, what's the one thing you hope people remember?

Speaker #1 - I think it's this. Our ideas about hygiene, they're always changing. What one generation thinks is clean, the next might think is totally gross. It's all relative, you know?

Speaker #0 - And what we think is normal now, maybe our grandkids will think it's weird.

Speaker #1 - Totally. Like all the antibacterial stuff. What if they figure out new stuff, discover new microbes, or realize being too clean is actually bad for you?

Speaker #0 - Yeah, it makes you think, doesn't it? Today, we've gone from 16th century Geneva to modern showers to who knows what's next. It's been a trip, hasn't it?

Speaker #1 - It has. It's amazing how much you can learn from something as simple as hygiene. It tells you about culture, science, how society changes.

Speaker #0 - So as you're going about your day washing your hands, maybe think about all this. How we got to where we are and where we might be going next.

Speaker #1 - Great point. Who knows what the future holds? Maybe sonic showers or nanobots that clean your pores. Sounds kind of fun, actually.

Speaker #0 - That's a deep dive for another day. But for now, thanks for joining us on this journey through the history of hygiene. It's been fun and hopefully a little thought-provoking too.

Speaker #1 - It has. Always fascinating to dig into these everyday things and see what we can learn.

Speaker #0 - And who knows, maybe we'll be back to scrub up some more fascinating topics in the future. Until then, stay clean, stay curious, and keep exploring.

Sources

By Dr. Christophe Chazalon (2024)

To fully understand Genevan history, the first essential notion to grasp is that of family structure. In Geneva, under the Ancien Régime, patriarchy reigned in its ancient Hebrew and non-feminist version, it goes without saying. The patriarch, which literally means "the command of the father," accumulated all powers there.[01] He is at the head of a household (or "feu" ("fire"), or "maison" ("house"), or "ménage", which would correspond today to an "cellule familiale élargie" ("extended family cell") that he directs as he sees fit. Woman, children, other family members who live with him, servants, are under his responsibility, as well as all the property of the household members, whether undivided or not. In Geneva, the patriarch or "chef de maison" is generally the husband, but not always. He may be the oldest brother (the "fils de famille") or an uncle, or even a "tuteur" ("guardian") (generally chosen from among close relatives), but it is always a male. And we specify the oldest brother and not the elder brother, because if the latter has founded a new household, the person in charge may sometimes be a younger brother.

In fact, this hierarchical structure stems directly from Roman law as Dominique Youf clearly summarizes:

« S’il n’est pas d’âge de la majorité en droit romain puisque le fils ou la fille de famille restent sous la patria potestas, il n’est pas rare que le pater familias meure avant que ses enfants soient devenus adultes, le taux de mortalité étant élevé. Le fils de famille devient alors pater familias ; même s’il n’est pas encore pubère, il est sui juris. Cependant, l’enfant qui vient de naître n’est pas capable de défendre ses intérêts. Le droit romain a donc été contraint de mettre en place des seuils d’âge par lesquels le pupille voyait se développer sa capacité juridique. Jusqu’à la puberté, c’est-à-dire jusqu’à l’âge de quatorze ans, le pupille est sous tutelle ; ensuite il est sous curatelle jusqu’à l’âge de vingt-cinq ans, âge auquel il devient véritablement pater. Les pupilles, qu’ils soient garçons ou filles, peuvent tester à l’âge de la puberté alors que cela est impossible aux enfants sous puissance paternelle. Cela ne signifie pas que les enfants sous puissance paternelle ne pouvaient passer d’actes juridiques. Mais ils le faisaient au nom du père, tout comme l’esclave le faisait au nom de son maître ».[02]

In this context, women are relegated to the role of "femme au foyer" who must bear and raise children.[03] They also take care of household chores if the household is too poor to have servants, and this with the help of the daughters of the family if there are any. For wealthier households, women can work alongside, in the family business or in trade, as a reseller, innkeeper, baker, roaster, for example... It happens, however, that some women become responsible for the family business, such as a printing house or a tavern, following the departure or death of the husband. Another notorious case: if there is a divorce or death of the husband, the woman is entitled to recover her dowry and her personal effects which, although managed by the husband, are still her property.[04] Similarly, in case of condemnation of the husband to the capital penalty, with the difference that here, the rest of the property is seized by the authorities. Finally, in the context of an office, the woman sometimes works just as much as her husband without being granted a proper salary.[05]

Before going any further, it must be remembered that it is not so much out of machismo that the society of the time was patriarchal, as today's feminists might want to make it understood. Certainly, men wanted (and still want) power, domination...[06], but two very different factors existed at the time and have completely disappeared today: one relates to public health, the other to state finances. Public health under the Ancien Régime was very poor, both for reasons of undernourishment, precarious medicine and lack of hygiene. Laundry is indeed done there (the "bues") and there are indeed stoves in the city (a kind of public baths), but both have a cost that is not accessible to a good part of the population.[07] Moreover, in fact, the stoves serve mainly as meeting places where people eat, drink, sleep and more if affinity... Calvin and his cronies are offended by this more than once (without much success however), because they cannot stand the very great promiscuity between men and women that reigns there.[08] Added to this are the horsemen of the Apocalypse (wars, famines and plague (or other epidemics, including smallpox much more deadly for babies and children)) which mistreat the population with constancy and vigor. Death then invites itself into daily life. It is omnipresent in the lives of families and particularly affects children. It is commonly accepted that at that time, « la mortalité infantile élimine un enfant sur deux » ("infant mortality eliminates one in two children") in the year following birth, and that "50% des survivants n’atteignent pas l’âge adulte" ("50% of survivors do not reach adulthood"), or more simply put: barely 25% of babies become adults, while "la vieillesse commence à quarante ans" ("old age begins at forty").[09] This has implications for the vision of the afterlife, therefore on religious beliefs and therefore, on the advent of the Reformation, but also on the management of property. If each individual managed his property, under such conditions, the question of inheritance would very quickly become problematic. Also, centralized management and a majority of property by indivision promote greater flexibility in the face of the high mortality rate. This is why in Geneva, as in the neighboring Pays de Vaud, a particular form of indivision is practiced. In fact, if the "chef de famille" manages the entire patrimony, only half of it belongs to him. The other half belongs to his children. This half is called the "légitime."[10] The "chef de maison" cannot dispose of it as he pleases, like the dowry of his wife. Even if he makes the final decisions, he must be accountable. And for state finances, the calculation is also much simpler, as the examples below show. It suffices to evaluate the property as a whole for a household rather than having to consider each property of an individual independently, knowing that often this individual owns only part of one or more land properties. Thus, the logic of the Ancien Régime is the reverse of that promoted by the current finance ministries, which wish to obtain as much detail as possible to optimize tax collection.

*******

Michel Serres recalls, in his pamphlet C’était mieux avant, not without irony, "avant, nous faisions la lessive deux fois l’an, au printemps et à l’automne ; en langue d’oc, la mienne, cette cérémonie s’appelait la bugado. […] La périodicité de cette grand-messe semestrielle signifiait que nous ne changions les draps de nos lits que deux fois l’an, ainsi que nos chemises sur le dos, et nos mouchoirs dans les poches. […] Chimique et théorique depuis Pasteur, dès le XIXe siècle, ou avant lui, depuis Semmelweis, l’hygiène ne devint une pratique généralisée que longtemps après 1950. En ces dates de mon enfance, le magazine Elle se lança non sans fracas en recommandant aux femmes de changer de culotte tous les matins. Chacun en riait sous cape, la plupart se scandalisaient, le reste trouvant impossible une telle exigence. Cependant, la renommée de cette revue vint de cet appel." [11]

In fact, this scientific study by Giroud, in a way, launched Elle magazine. However, historians and scientists today look upon it unfavorably, because it is a women's magazine, considered anything but scientific and serious. However, the study was and, moreover, served as a comparative basis for a new study conducted in February 2020, in France, by IFOP, entitled "1951-2020: évolution des comportements d'hygiène corporelles et domestiques. Les Français(es) sont-ils propres?" (1951-2020: Evolution of personal and domestic hygiene behaviors. Are the French clean?)"[12]

The conclusion of the study is that the proportion of women washing daily increased from 52% in 1951 to 74% in 1986 (IPSOS study) and 81% in 2020. For men, we do not have the statistics, but in 2020, 71% perform a complete wash "au moins une fois par jour" ("at least once a day") 24% twice a week and 5% once a week.

So no, the inhabitants of Geneva in the Sixteenth-Century did not bathe every day at the stoves, or every week, or every month, reinforcing Michel Serres's comments on hygiene before 1950 in France. For simple reasons, including these three main ones in the sixteenth century:

- The Church forbade bathing (and the Protestants followed suit), even in the lake (especially since people could not swim), certainly for reasons of promiscuity and nudity, but mainly because it was then believed that this promoted disease. Water promoted the spread of "humeurs" (naucives). "Humeur" borrowed from the Latin "humor," is what is wet, humid. Originally, it has a purely medical sense, but with the evolution of medicine researchers isolated and defined the liquids of the human body; gradually the term humor fell into disuse." So at most, we were cleaned with wet towels or squirting water in the face, then drying. As for the change of clothes, almost all of the population had only one for every day of the week, clothes that were worn until worn out (with perhaps an outfit for holidays, weddings, baptisms, funerals, etc.). That's it! Same underwear. Only the richest, the nobles and notable bourgeois possessed a "garde-robe" provided, made it wash etc.

- The stoves are heated, so it has a cost in firewood, which is reflected in the price of use by users who are not affordable for everyone, nor for a daily or weekly visit.

- There are then only 2 stoves in Geneva, at best 3 following years, for a city that has about 7,000 inhabitants, without forgetting the merchants, passers-by, vagabonds of all kinds. It is hard to see how they could contain all this world.

So to say that the Genevans under Calvin or Théodore de Bèze washed daily, or even every week, in other words, that they had even relatively constant bodily hygiene is an error, as several studies on the West in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance have described. [13]

*******

Calvin tries every year to separate men and women in the public baths, without real success, because not only are the "étuves" primarily a meeting place where people eat, sleep, wash and more if affinity, but even more so because the "étuves" are a kind of brothel, an old-fashioned "maison close", which is part of a "thermale" setting. So the people who go there, including pastors (yes! they are not so pure), are above all libertines, fornicators, lovers of the pleasures of all flesh.[14]

Notes:

[01] https://nouveautestament.github.io/lemme/%CF%80%CE%B1%CF%84%CF%81%CE%B9%CE%AC%CF%81%CF%87%CE%B7%CF%82.html, and https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patriarcat_(sociologie).

[02] Dominique Youf, « Seuil juridique d’âge : du droit romain aux droits de l’enfant », Société et jeunesse en difficulté : revue pluridisciplinaire de recherche, n° 11 (printemps 2011), p. 4 (http://journals.openedition.org/sejed/7231). Note the distinction between “curatorship” and “tutorship” which also prevailed in Geneva at the time of the Reformation.

[03] This extract from the General Hospital register is particularly eloquent on the subject: "(Des filles de ceans qui vivent de l’aumosne) — Ces filles qu’estudient, est resolu qu’elles apprennent [à] prier Dieu, ses commandementz, et du reste, qu’elles soient instruictes à tailler une chemise, ung covrecol et à rabiller des chausses, des robbes, etc., et former les livres pour les filz masles" ("(Of the girls here who live on alms) - These girls who study, it is resolved that they learn to pray to God, His commandments, and for the rest, that they be instructed to cut a shirt, a head covering and to mend stockings, dresses, etc., and form the books for the male sons.") (A.E.G., Archives hospitalières Aa 1, fol. 129v° (03 février 1544)). However, this point of view must be put into perspective, as Anne-Marie Piuz rightly points out: " à quelques achats près, comme le bois, et encore, toutes les dépenses des ménages sont des dépenses de femme et si on rappelle que, dans les sociétés traditionnelles, les ménages constitutent globalement la principale demande, on peut avancer que près de 80% des dépenses de la majorité de la population sont effectués par les femmes. L’importance des femmes dans l’économie saute aux yeux : elles détiennent une grande part du pouvoir financier en gérant les ressources du ménage. […] Pour les femmes mariées, modestes et pauvres, c’est-à-dire la majorité, c’est une occupation à plein temps ou presque que la responsabilité de la nourriture de chaque jour." ("except for a few purchases, such as wood, and even then, all household expenses are women's expenses, and if we remember that in traditional societies, households as a whole constitute the main demand, we can argue that nearly 80% of the expenses of the majority of the population are made by women. The importance of women in the economy is obvious: they hold a large share of financial power by managing household resources. [...] For married women, modest and poor, that is to say the majority, it is a full-time or almost full-time occupation that the responsibility for the food of each day.") (Anne-Marie Piuz, "Les activités urbaines", in Simonetta Cavaciocchi (ed.), Atti della 21esima settimane di studi dell’Istituto di storia economica F. Datini (10-15 aprile), Florence: Le Monnier, 1990, pp. 131-136, passage cité dans Liliane Mottu-Weber, "L’insertion économique des femmes dans la ville d’Ancien Régime. Réflexions sur les recherches actuelles", in Anne-Lise Head-König / Albert Tanner (ed.), Frauen in des Stadt. Les femmes dans la ville, Bern: Chronos, 1993, p. 31 (Société Suisse d’histoire économique et sociale, vol. 11)). [https://www.e-periodica.ch/digbib/view?pid=sgw-001:1993:11::222#27]. Voir également Liliane Mottu-Weber, "L’évolution des activités professionnelles des femmes à Genève du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle", in Cavaciocchi, 1990, pp. 345-357.

[04] This is the case, for example, of Jacot, widow of Pierre Vellu, in 1540; Jeanne Vallet, widow of Thivent Volland, in 1541; of Pernette Monathon, wife of the Savoyard Michel Yssuard, in 1541-1542; of Jeanne Duvillard, wife of Maurice Delarue, in 1543, or even of Pernette de La Rive, known as la Magestria, widow of the notary Pierre Magistri, in 1544 (R.C. impr., n.s., t. V/1, p. 39 (13 janvier 1540); t. VI, p. 258 et n. 53, et 328 et n. 113 (06 mai et 21 juin 1541); t. VII/1, p. 192-193 et n. 109, et p. 506 et n. 90, annexe 87 (11 avril et 17 octobre 1542 ); t. VIII/1, p. 31-32 et n. 102 (16 janvier 1543) et t. IX/1, p. 30 et n. 83 (15 janvier 1544)). On marriage and divorce in Geneva at this time, see Robert M. Kingdon, Adultery and divorce in Calvin’s Geneva, Harvard : Harvard University Press, 1995, 224 p.; Cornelia Seeger, Nullité de mariage, divorce et séparation de corps à Genève, au temps de Calvin, Genève : SHAG, 1989, 502 p.; Marie-Ange Valazza Tricarico, Le régime des biens entre époux dans les pays romands au Moyen Âge: comparaison des droits vaudois, genevois, fribourgeois et neuchâtelois (XIIIe – XVIe siècle), Lausanne: Société d’histoire de la Suisse romande, 1994, 313 p. et Jeffrey R. Watt, The Consistory and social discipline in Calvins Geneva, Woodbrigde (GB): Boydell & Brewer / Rochester (NY/US): University of Rochester Press, 2020, pp. 100-137. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv10vm05k.9]

[05] On January 28, 1542, Jean Fontaine takes office as the new hospitaller of the General Hospital. However, two days later, the hospital's attorney, Jean Chautemps, appears before the Small Council, because the hospitaller, that is, Jean Fontaine's wife, is claiming a salary for her work. The Council decides "que cella soyt mys bas, voyeant que l’on n’est en coustume de ce fere" ("that this request be denied, as it is not the custom") (R.C. impr., n.s., t. VII/2, p. 52 (ad diem)).

[06] To be convinced of this, one only has to consider the difficulty encountered today in implementing parity in companies or the political world.

[07] "This refers to the study by Françoise Giroud, "La Française est-elle propre?" ("Is the Frenchwoman Clean?"), published in Elle magazine on October 22, 1951. See above and note 11.

[08] R.C. impr., n.s., t. VII/1, p. 186 (07 avril 1542); t. VIII/1, p. 111 et 114 (02 et 05 mars 1543): "que ung chascun homes et femmes soyent separés, synon qu’il soyent conjoient en mariage, et allors peulve coucher ensemble, non pas estuver" ("that all men and women should be kept separate, unless they are joined in matrimony, in which case they may sleep together, but not bathe together"); A.E.G., R.C. 40, fol. 273 et 284v° (26 octobre et 06 novembre 1545); A.E.G., R.C. 42, fol. 87 (15 avril 1547) et A.E.G., R.C. 43, fol. 101 (28 mai 1548)).

[09] https://www.larousse.fr/encyclopedie/divers/Ancien_R%C3%A9gime/105343 et Marie-France Morel, "La mort d’un bébé au fil de l’histoire", Spirale, n° 31, 2004/3, pp. 15-34 [https://www.cairn.info/revue-spirale-2004-3-page-15.htm]. It should be noted that the "legal" age of marriage in Geneva, with the mandatory consent of relatives, was at that time 12 years for girls and 14 years for boys. As for "old age," one only has to consider the age of the magistrates (syndics). In 1534, Michel Sept was elected at the age of 37 and Jean-Ami Curtet at 35; in 1535, Ami Bandière was elected at 41; in 1536, Étienne Chapeaurouge was elected at 36; in 1537, Claude Bonna, known as Pertemps, was elected at 28; in 1538, Jean Lullin was elected at 51; in 1542, Claude Roset was elected at 42 and Amblard Corne at 28, and in 1544, Antoine Gerbel was elected at 29 (Christophe Chazalon, "Les Conseils de Genève de 1534 à 1544 à travers les registres", in Catherine Santschi (éd.), Les registres du Conseil de la République de Genève sous l’Ancien Régime : nouvelles approches, nouvelles perspectives, Genève: A.E.G., 2009, pp. 73-74 [https://chazalonchristophe.com/geneve.html]

[10] For a greater understanding of "légitime" ("legitimate"), see Jean-François Poudret, "La dévolution ascendante et collatérale dans les droits romands et dans quelques coutumes méridionales (XIIIe – XVIe siècles", Revue historique de droit français et étranger, n° 4, 1976/10-12, pp. 509-532 [https://www.jstor.org/stable/43846221], ainsi que Marta Peguera Poch, Aux origines de la réserve héréditaire du code civil: la légitime en pays de coutume (XVIe-XVIIe siècles), Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires d’Aix-Marseille, 2015, 353 p. [https://books.openedition.org/puam/885].

[11] Michel Serres, C'était mieux avant, Paris: Éditions Le Pommier, 2017, pp. 28-31. This refers to the study by Françoise Giroud, "La Française est-elle propre?", published in Elle magazine on October 22, 1951. [http://chez-jeannette-fleurs.over-blog.com/la-francaise-est-elle-propre-magazine-elle.francoise-giroud.lundi-22-octobre-1951]

[12] https://www.ifop.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Rapport_Ifop_Diogene_2020.02.25c.pdf

[13] See the bibliography below.

[14] This example taken from the Registers of the Council of Geneva shows it: "que ung chascun homes et femmes soyent separés, synon qu’il soyent conjoient en mariage, et allors peulve coucher ensemble, non pas estuver" ("that all men and women should be kept separate, unless they are joined in matrimony, in which case they may sleep together, but not bathe together"). (R.C. impr., n.s., t. VII/1, p. 186 (07 avril 1542) ; t. VIII/1, p. 111 et 114 (02 et 05 mars 1543); A.E.G., R.C. 40, fol. 273 et 284v° (26 octobre et 06 novembre 1545) ; A.E.G., R.C. 42, fol. 87 (15 avril 1547) et A.E.G., R.C. 43, fol. 101 (28 mai 1548)).

And much more

Here are some suggestions for continuing the discovery of hygiene in the Middle Ages and the Ancien Régime:

- Danièle ALEXANDRE-BIDON, "Pas de bains pendant mille ans? Les principes de l'hygiène au Moyen Âge", Histoire et images médiévales, n° n/a, 2009/08-09, p. 1-8 (web)

- Evelyne BERRIOT-SALVADORE, Un corps, un destin: la femme dans la médecine de la Renaissance, Paris, Champion, 1993, 282 p.

- Maurizio BIFULCO / Mario CAPUNZO / Magda MARASCO / Simona PISANTI, "The basis of the modern medical hygiene in the medieval school of Salerno", The journal of maternal-fetal and neonatal medicine, vol. 28, n° 14, 2015, pp. 1691-1693 (web)

- John H. BRYANT / Philip RHODES, "History of public health: the Middle Ages", in Britannica, 2025/02, online (web)

- Mark CARTWRIGHT, "Medieval hygiene", in World history encyclopedia, 2008/12, online (web)

- Albrecht CLASSEN, Bodily and spiritual hygiene in Medieval and Early Modern literature: explorations of textual presentations of filth and water, Boston (MA): Walter de Gruyter, 2017/03, 622 p. (coll. Fundamentals of Medieval and Early Modern culture, 19)

- Patrice CRESSIER / Sophie GILOTTE / Marie-Odile ROUSSET, "Lieux d'hygiène et lieux d'aisance au Moyen Âge en terre d'Islam", Médiévales, n° 70, 2016/04-06, pp. 5-12 (web)

- Magdalena LANUSZKA, "Scrub-a-dub in a Medieval tub: contrary to popular misconceptions, Europeans in the Middle Ages took pains to keep themselves clean", in JSTOR Daily, 2023/11, online (web)

- Shannon QUINN, "Strangest hygiene practices from the Middle Ages", in History collection, 2020/12, online (web)

- Georges VIGARELLO, Le propre et le sale: l'hygiène du corps depuis le Moyen Âge, Paris: Le Seuil, 1985, 285 p. Translation: Concepts of cleanliness. Changing attitudes in France since the Middle Ages, Cambridge / New York / Melbourne...: Cambridge University Press, 1988, 239 p.: by Jean Birrell (web)

*******

RCnum PROJECT

This historical popularization podcast is developed as part of the interdisciplinary project entitled "A semantic and multilingual online edition of the Registers of the Council of Geneva / 1545-1550" (RCnum) and developed by the University of Geneva (UNIGE), as part of funding from the Swiss National Scientific Research Fund (SNSF). For more information: https://www.unige.ch/registresconseilge/en.